Reading time:

short story - novelette - novella - novel - PhD thesis - War and Peace - U.S. Tax Code

Also available with a translator, 🇫🇷 🇪🇸 🇩🇪 🇯🇵 etc:

Any extracts used in the following article are for non-commercial research and educational purposes only and may be subject to copyright from their respective owners.

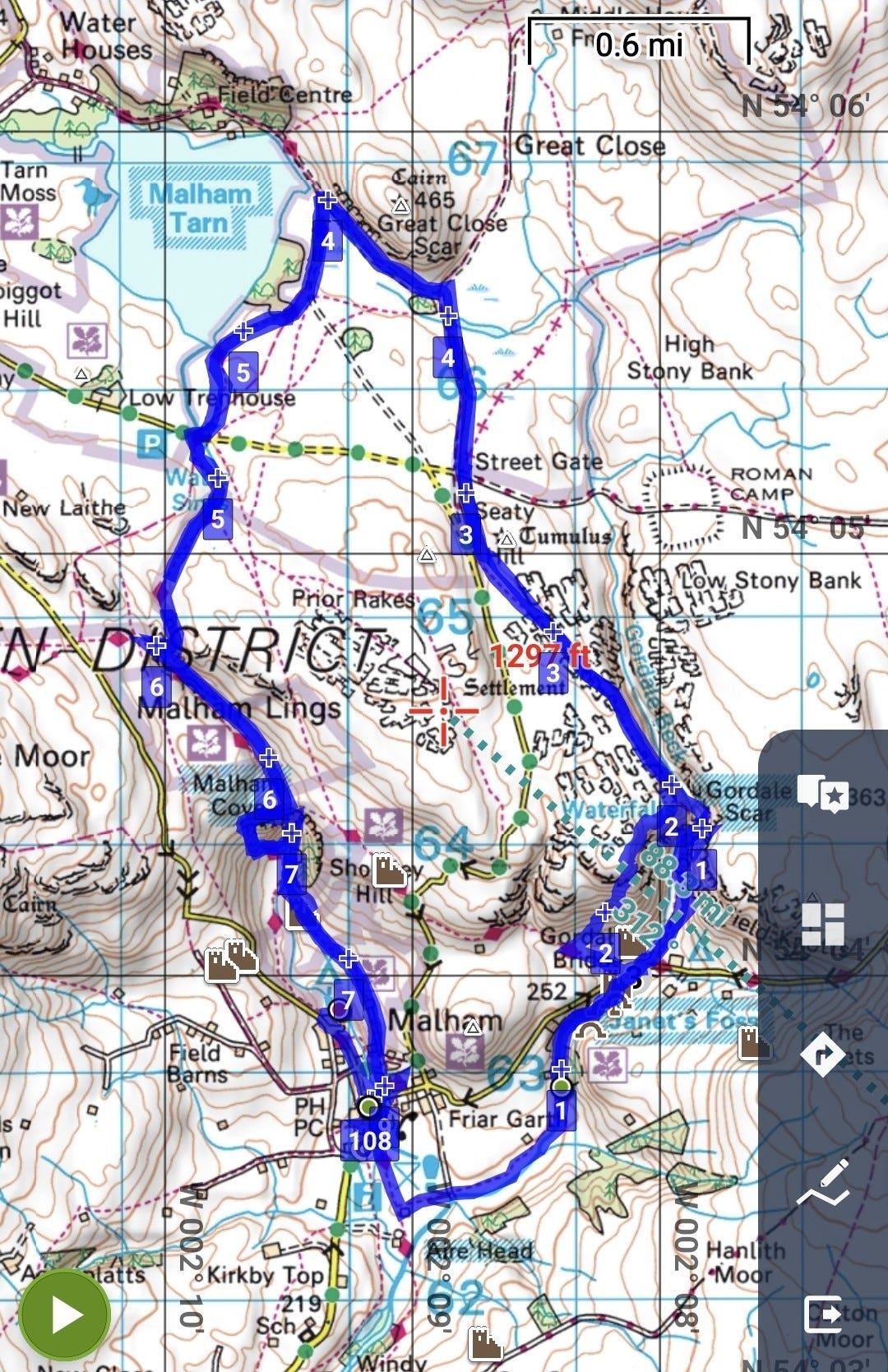

Walk overview

Start: Malham Village

Ordnance Survey (OS) Map: Yorkshire Dales - Southern & Western Area

Whernside, Ingleborough & Pen-y-ghent. OL2. 1:25,000

Grid Reference: SD900427

Public Bus Timetable

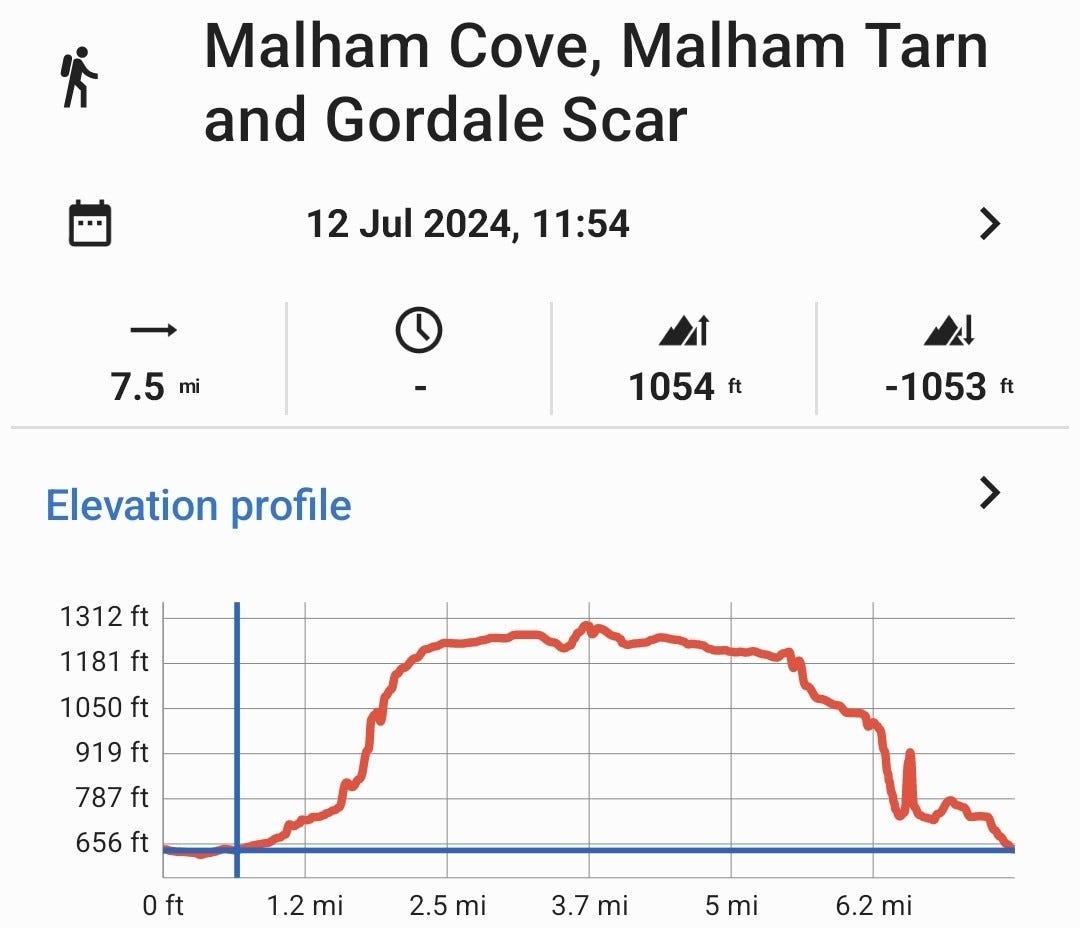

Distance: 7.5 miles / 12.0 km

Time: 3-4 hours, although I took a lot longer, with photo stops and backtracking around Gordale Scar.

Climb: 1007‘ / 307m

GPX Route Download

Google Earth Download

Android App: Locus Map

OpenAndroMaps Downloads for Android: Link

Guide to Adding Bing + OS Maps to Locus Maps Classic: Link (This is being deprecated by Microsoft and not ported over to Azure).

Website with OS Maps: Link

Garmin OpenTopo Downloads: These are near OS quality and include Basecamp files & DEM contours: Link

Further Reading: How to use OpenStreetMap and OS digital maps

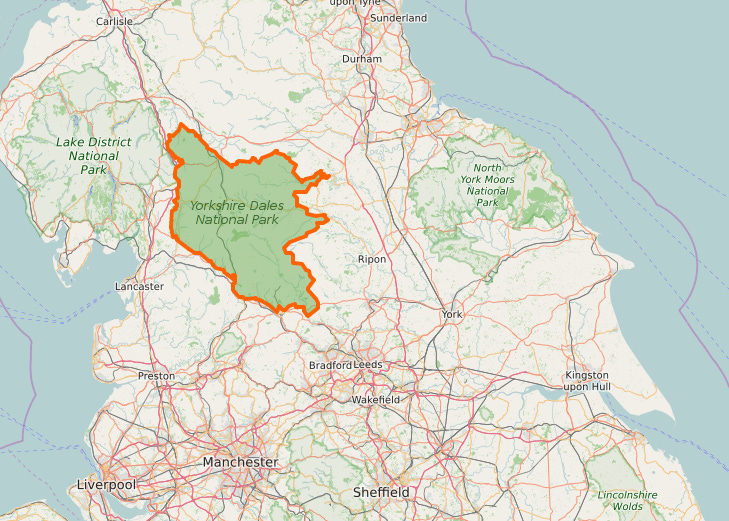

The Yorkshire Dales National Park

The park was designated in 1954 and extended further west in 2016, increasing the area by nearly 24%. It now covers 841 sq mi (2,178 km2), is home to 23,500 residents and attracts more than four million visitors annually.

Driving up from the South, you slowly leave behind the urban sprawl of the formerly industrial towns filling the Aire Valley and southern Pennine hills.

The nearer you get to Malham the narrow the roads get, and for the last 8 miles from Gargrave it’s a challenging drive that needs your full attention, twisting and turning, with blind humpback bridges to catch out the unwary.

Just as you begin to question your sanity you see a huge wall of limestone on the horizon.

I don’t like adding to a hike with extra miles just to get you from the campsite, so I stayed at the Riverside Campsite, almost on the route. I can well recommend this site, but it is an example of ruling by poster. And they are everywhere. They adorn every wall and gate to keep unruly guests in check.

At one point I thought I might get chucked out.

I was using my Whisperlite stove on wet grass, as I’ve always done, and it did burn a hole in the turf. You have to preheat this type of petrol stove by flooding it with fuel. The next time I used it, the now flammable grass caught fire, which speeded up the preheat somewhat, but did turn it into a bit of a flame thrower.

Later on I saw a sign by a gate: "No burners on grass - use firebricks provided”.

Oops.

Apologies Mrs M.

I confess it was me.

This loop is the most popular walk in the National Park, and you can see why. Although lacking the splendour of the Alps, Rockies or the Scottish Highlands it’s still a very scenic walk and steep in places.

You can start the walk from anywhere on the loop. I set off South from the village, paralleling Malham Beck for a short distance before heading East across water meadows towards Janet’s Foss.

Our first limestone pavement:

The white or creamy flower heads (cymes) are meadowsweet (Filipendula ulmaria). They have a sickly sweet smell and prefer damp locations.

I thought I’d seen a thistle at first, but these are most likely common spotted orchids (Dactylorhiza fuchsii).

Despite the name, they are only locally common in the UK, due to habitat loss.

Different Dactylorhiza species readily hybridize where their ranges overlap, which makes identification quite challenging.

Janet’s Foss has a drop of about 16‘ / 5m.

Legend has it that it is named after a fairy queen (Janet or Jennet) who is said to reside in a cave behind the waterfall. I didn’t see her that day though.

The path climbs up to the left, and poles are useful in places.

Turning right along Gordale Lane you pass a handy burger van, bear right and then head through a gate towards Gordale. It‘s been easy going so far, and not much of a navigational challenge.

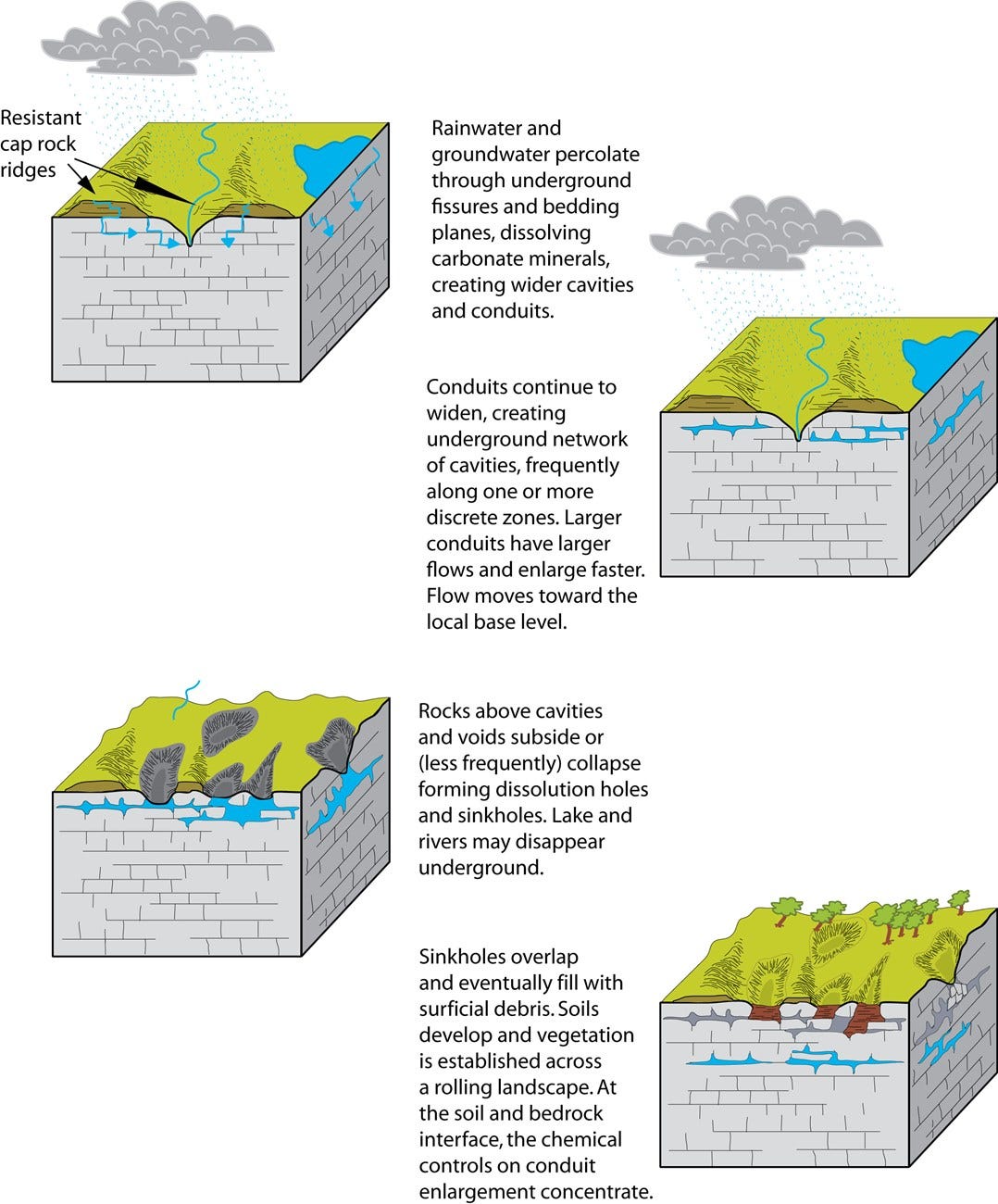

The area’s carboniferous limestone and tufa are derived from sediments deposited in a shallow tropical sea, around 340 million years ago.

The deep limestone gorge we see today formed during the last ice age, as meltwater from glaciers eroded a gorge created from a collapsed cavern.

Imagine being near it and feeling the earthquake as an enormous volume of rock plunged into the glacial river below, which was then probably dammed for a time.

For those into rock climbing, Gordale has several challenging grade 7 & 8 climbs, some of the toughest in the country.

Rockfalls are always a risk, due to the overhanging 330’ / 100m high cliffs.

A sign warns you of this, and water dripping on your head from the cliffs above reminds you not to hang around too long.

Lower Gordale Scar waterfall has a double drop of about 131’ / 40m, the upper falls a single drop of around 23’ / 7m.

This part of the walk is described as “technical” or a “scramble, and you wouldn’t attempt it after heavy rain unless you want a face full of water.

The usual route up the far left wasn’t an option for me for this reason.

I decided to watch and wait a few minutes to find another way up, as some routes can look far easier close-up than from a distance.

This was not to be one of those climbs. The only chap who succeeded had climbing shoes and a low-profile lightweight pack. Fearing certain death, I decided to backtrack and go around.

I took the path West from the burger van, and headed up the steep climb to the plateau at 1200’ / 365m.

This was an occasion where OpenStreetMap was better for finding a path up New Close Knotts than the OS map.

The OS map lacks this level of path detail, and makes it look un-climbable:

A clump of common rockrose (Helianthemum nummularium) on the climb up:

I was rewarded for my efforts with a fantastic view South over the Dales.

Being careful for a second time not to fall to my doom, I peered over the edge:

The bottom of the gorge is about 400’ / 121m below.

The original route below, by the beck, merges with the diversion a little further on, after a climb up from the gorge.

The pace picks up on the plateau as you follow a grassy path for a mile or so.

You eventually find yourself walking through a strange, alien, boulder-strewn landscape leading up to New Close.

At the Great Close Plantation you do a 90° left turn, skirting the lower slopes of Great Close Hill.

On your left is some impressive calcareous marshland (i.e. fenland), with common spotted (D. fuchsii), northern marsh (D. purpurella), southern marsh (D. praetermissa), early marsh (D. incarnata), and their hybrids all around.

Malham Tarn is where you hang another sharp left, to make your way back to Malham.

One of the UK’s rarest plants, the Lady’s Slipper Orchid (Cypripedium calceolus), has been reintroduced somewhere near here. It’s a spectacular plant and thanks to micropropagation readily available now to growers.

I did keep one of these alive long enough to flower, but sadly it didn’t survive the winter.

There is a saying: “Horses are on a lifelong mission to kill themselves in every way possible”.

Cypripedia are a bit like that.

They don’t like it too dry.

They don’t like it too wet.

They don’t like it too warm.

They don’t like exposing to a hard frost.

And they don’t like direct sun. Or over-feeding. Or being windswept.

And the pH needs to be OK too.

With their appeal to unscrupulous collectors, it’s a miracle they survive at all.

Back on track and heading South I’m always looking out for anything unusual, and I spotted an insectivorous plant, the common butterwort (Pinguicular vulgaris). They are so named as the leaves were traditionally used in Europe to curdle milk for cheese making.

The plants are adapted to growing in low-nitrogen soils, but the protein content of their seed is nitrogen-rich. Setting seed is quite demanding on the plants, this is thought to be the main reason why the leaves evolved into fly papers.

More D. fuchsii, with a spectacular backdrop.

You can see seed capsules forming on these pinguicula.

Focusing was off here, but I suspect this is a southern marsh orchid (D. praetermissa):

Eventually, briefly following the Pennine Way, you leave the lowland fen behind and start descending past Comb Hill Crag towards Watlowes.

Needing a hairpin left, you are safer with poles for the next leg. Watlowes is the dry riverbed of a once substantial river that used to flow over Malham Cove.

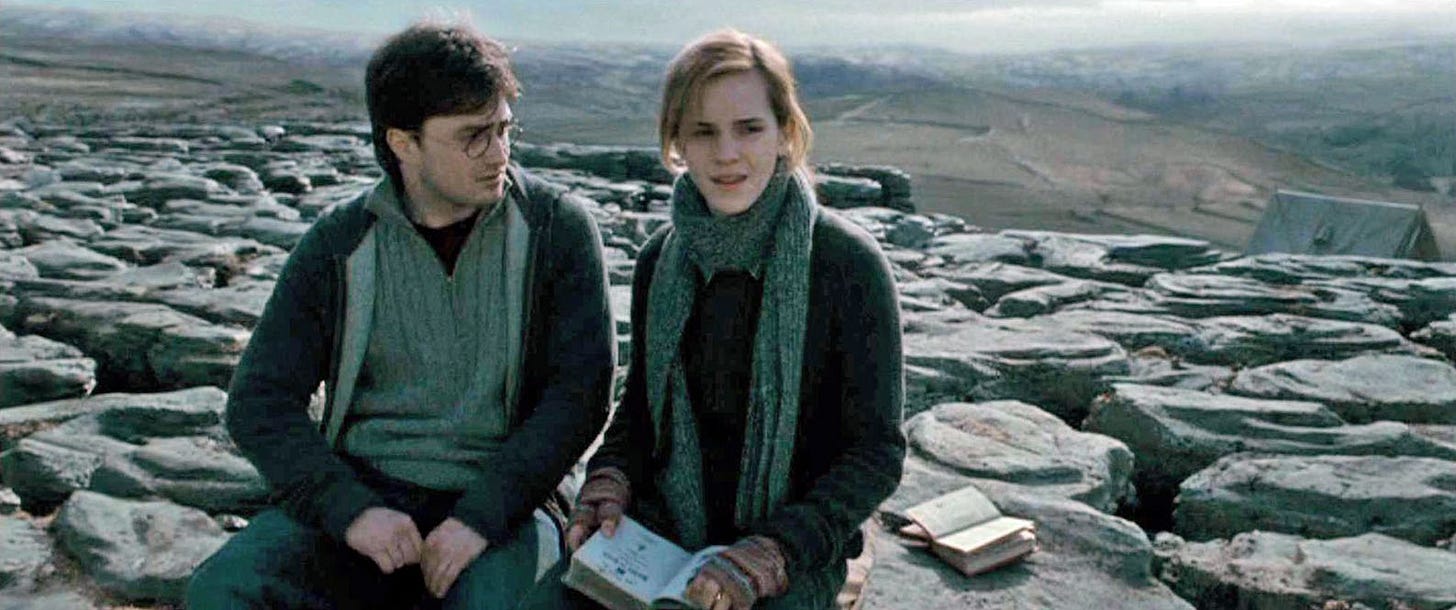

The eroded limestone pavement of the cove is typical of a glacially affected karst landscape, or glaciokarst.

Our second limestone pavement of the day ;-)

Some of these move as you step on them.

I came on the first dry day for ages. It’s safer if the rocks have dried out.

Several ferns grow in the grikes, out of reach of the many sheep grazing the area. These include harts-tongue (Asplenium scolopendrium), the limestone fern or scented oakfern (Gymnocarpium robertianum), rigid buckler fern (Dryopteris submontana), and holly fern (Cyrtomium falcatum).

Malham village below, with a well-marked and popular path on the right.

You might recognise the limestone pavement from the Harry Potter film “The Deathly Hollows”.

If you did pitch up there you would need a good thick roll mat.

There are about 300 steps down to the foot of the cove, which towers over 260’ / 80m above you. You can picture it in the last Ice Age, with a glacial river plunging over the top.

I’ve seen water going over it after heavy rain. Although nothing on the scale seen in the Ice Age it gives you an idea of how it was, and Wiki has an entry:

I tested how waterproof my boots were by crossing the beck to resume the return to the village. This route avoids the tourist path, but did present its own challenge.

I had to yomp uphill to the drystone wall on the right to get around these guys. They looked placid enough, but you just never know how they might react.

I finally made it to the Listers Arms, some 10 miles and several hours later.

I can tell you, it was a little like the scene in the classic war film from 1958.

Back at camp, the sun finally came out to round off a perfect day.

Further reading:

SatNav Corner

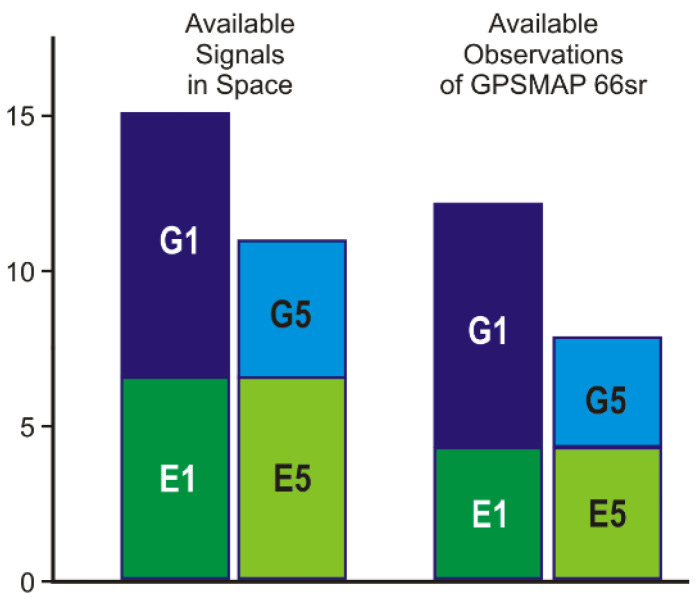

If you are missing a deep dive I came across a paper on PubMed, of all places, whilst checking out the accuracy of the new European Galileo GPS service with consumer-grade devices.

The short answer is that, for devices with a quad-helix aerial, GPS fix accuracy can be improved from about 10’ / 3m to 3.3’ / 1m.

How does it work?

A quadrifilar helix antenna is a type of antenna known for its circular polarization and omni-directional coverage, consisting of four helically wound conductors that are symmetrically spaced around a common axis. This design allows it to effectively transmit and receive signals in all directions, making it particularly useful for satellite communications, GPS systems, and meteorological satellites. Its unique structure provides stable performance across a wide range of conditions, ensuring reliable communication where consistent signal quality is critical.

A quadrifilar helix antenna (QHA) is a type of antenna that consists of four helical wires wound around a central axis. It is designed to receive circularly polarized signals, which are commonly used in satellite communications as well as RFID.

The QHA works based on the principle of helical radiation. When an alternating current is applied to the wires, electromagnetic waves are generated and radiated into space. The helical shape of the wires causes the electromagnetic waves to be circularly polarized. This means that the electric field vector rotates in a circular pattern as the wave propagates.

The QHA is specifically designed to receive circularly polarized signals. It has a wide bandwidth and a high axial ratio, which means it can receive signals with different frequencies and polarization orientations. The axial ratio is a measure of how well the antenna can receive signals with the desired polarization.

The four helical wires of the QHA are arranged in a specific configuration to achieve circular polarization. Two of the wires are wound in a clockwise direction, while the other two are wound in a counterclockwise direction. This arrangement creates a balanced and symmetrical antenna structure, which helps to reduce unwanted signal reflections and improve performance.

In addition to receiving circularly polarized signals, the QHA can also transmit circularly polarized signals. When an alternating current is applied to the wires, the antenna radiates circularly polarized electromagnetic waves into space. This makes it suitable for applications such as satellite communication, where circular polarization is commonly used to overcome signal degradation caused by atmospheric conditions.

https://www.sannytelecom.com/what-is-a-quadrifilar-helix-antenna/

The theoretical peak accuracy for devices that can access all the Galileo bands is around 1 centimetre, and satellites are tracked and positioned in orbit with centimetre-level precision. We are all familiar with E = mc2. For this level of accuracy, you need to use atomic clocks and measure timings down to billionths of a second, i.e. a nanosecond. Light moves about 1’ / 30cm in a ns. By timing signals from synchronised satellites, you can triangulate distance and position.

The Garmin GPSMAP 6x series features a quadrifillar antenna and has been available since 2005. Although not very compact, it has earned a lot of respect for its ruggedness and accuracy when used in ravines or heavy forest cover - where there is a limited view of the sky. It’s the tool of choice for many search and rescue teams.

I have recently acquired a GPSMAP 64s, but it doesn’t access the Galileo bands. Later more expensive models do though, along with the Russian GLONASS and other bands, and accuracy in the field tops out at around 6’ / 1.83m

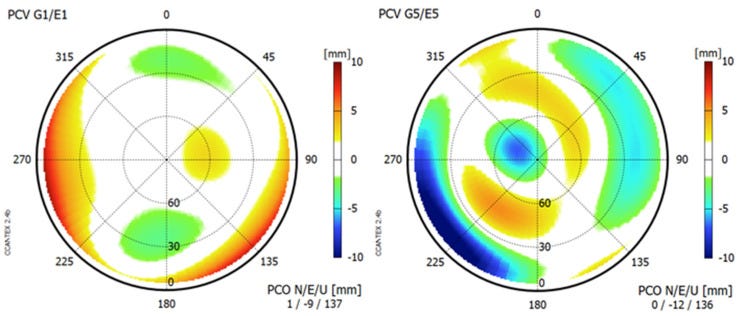

In 2022, Wanninger et al. decided to see if they could improve on this. And they did, not by a little, but down to 1cm, by performing dual-frequency GPS/Galileo precise point positioning (PPP). However, it took a lot of time, equipment and effort:

They needed a centimetre-accurate reference device for height readings.

They needed to perform phase-centre calibration on the antenna for hours.

They then needed to record static positional readings for many hours.

They needed to use the services of a local reference base station array, as well as their postprocessing error correction service.

It wasn’t exactly something you could use on a hike, but it shows how accurate such a relatively cheap, mass-produced device can be.

Key takes from “Garmin GPSMAP 66sr: Assessment of Its GNSS Observations and Centimeter-Accurate Positioning” (2022):

Abstract

In 2020, Garmin released one of the first consumer devices with a dual-frequency GNSS chip and a quadrifilar helix antenna: GPSMAP 66sr. The device is intended to serve as a positioning and navigation device for outdoor recreation purposes with positioning accuracies on the few meter level. However, due to its highly accurate GNSS dual-frequency carrier-phase observations, the equipment can also be used for centimeter-accurate positioning. We performed extensive test measurements and analyzed the quality of its code and carrier-phase observations. We calibrated the Garmin GPSMAP 66sr antenna with respect to its phase-center offset and phase-center variations. We also performed dual-frequency GPS/Galileo precise point positioning (PPP) and precise relative positioning in baselines to virtual reference stations (VRS). We demonstrate and explain how centimeter-accurate positioning can be achieved with this novel kind of equipment.

Keywords: Garmin GPSMAP 66sr, dual-frequency GNSS, carrier-phase observations, ambiguity fixing, phase-center calibration, postprocessing, centimeter-accurate positioning, precise point positioning (PPP), virtual reference station (VRS)

A great advantage of the GPSMAP 66sr in comparison with other consumer devices with dual-frequency GNSS chips, e.g., smartphones such as Xiaomi Mi8 or Huawei P30 [5], consists of its quadrifilar helix antenna (QHA).

QHA produces a circularly polarized hemispherical radiation pattern and, thus, is able to mitigate multipath signals [6].

It proved to be a major advantage of the equipment that GNSS observations can be stored internally in RINEX 3.04 format [7] and that these files can be easily transferred to a computer for postprocessing.

The GPSMAP 66sr is not designed to allow centimeter-accurate GNSS real-time positioning on the device itself. Therefore, it should be considered as a GNSS receiver with the potential to obtain centimeter-accurate positions in postprocessing only.

We performed and recorded several 100 h of GNSS observations with GPSMAP 66sr. Most of these datasets were collected in a roof-top environment without any signal obstructions and with low multipath levels (Section 3.1, Section 3.2, Section 3.3 and Section 4.1).

Further datasets originate from field measurements under adverse environmental conditions (Section 4.1 and Section 4.2). All these observations were performed in static mode, mostly at sites with precisely known coordinates from earlier determinations with geodetic-grade GNSS equipment.

The internal, rechargeable built-in lithium-ion battery lasted for at least 16 h in full GNSS mode (dual-frequency, all systems). For longer observation sessions, we used the external power supply via micro-USB.

Centimeter-accurate positioning in precise point positioning (PPP) mode or in relative mode requires additional data, such as precise GNSS orbit and clock information or GNSS observations from reference stations.

For analysis steps that required a local GNSS reference station, we used a Septentrio PolaRx5 receiver connected to a choke ring antenna of type Javad RingAnt-DM JVDM.

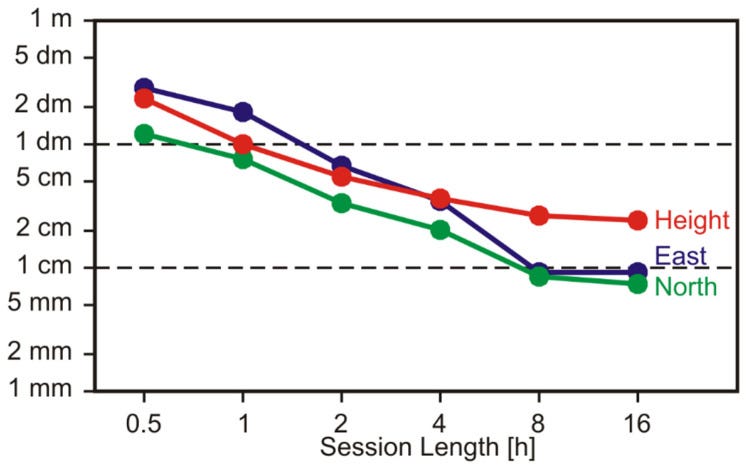

After 8 hours of recording, accuracy was down to 1cm laterally and about 3cm vertically:

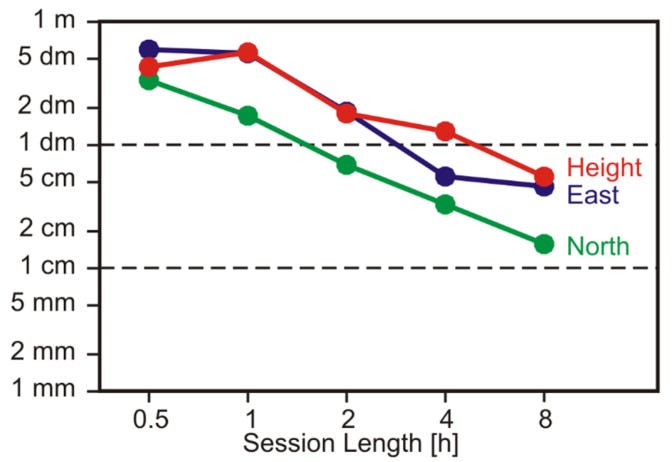

They then repeated the exercise at an adverse site, with trees and buildings around, and using a trekking pole for support. Results using this ad hoc setup were still excellent:

The RMS values of coordinate deviations of the remaining sessions are presented in Figure 16. The overall position accuracy is now considerably lower than that in our first trial at the roof-top site. Again, the north component is determined more accurately than the east and height components.

After just 30 min, the achieved accuracy is on the level of several 10 cm. A horizontal accuracy on the level of 10 cm (RMS) is obtained after 4 h, with even longer observation durations the results keep improving.

The postprocessing service computes virtual reference station (VRS) observations for the approximate user position (usually a few m off the final user position) and afterward runs a baseline processing between VRS and rover observations. More on this technique can be found, e.g., in [24]. The resulting coordinates of this service refer to the geodetic reference system ETRS89.

SAPOS-GPPS-PrO maintains a database of antenna phase-center corrections, which, of course, did not include the GPSMAP 66sr antenna. The service operators agreed to help by adding our calibration results (Section 3.3) to this database. Afterward, we could send the slightly modified Garmin RINEX files to the processing service and obtained positioning results.

We conclude that, with such a simple setup and with many hours of observations (virtually overnight), the GPSMAP 66sr is capable of providing ITRF coordinates on the level of 10 cm even at an unfavorable GNSS site.

5. Conclusions and Outlook

The Garmin GPSMAP 66sr (v3.30) offers dual-frequency GNSS observations for cm-level postprocessing applications. Due to its quadrifilar helix antenna, the observation quality exceeds the quality of other consumer devices with dual-frequency capability, e.g., smartphones. Centimeter-level positioning results can be achieved in long observation sessions (several hours), with precise point positioning (PPP), or in short observation sessions (many minutes) in baseline mode.

The main limitation of the device with respect to precise GNSS positioning is caused by the incompleteness of the tracked satellite signals. In particular, a higher priority of Galileo in the satellite selection process would considerably improve precise positioning results. If this problem is solved and with an increasing number of active Galileo satellites and more GPS satellites capable of transmitting G5 signals in the near future, the positioning performance will even exceed the level demonstrated in our trials.

Wanninger L, Heßelbarth A, Frevert V. Garmin GPSMAP 66sr: Assessment of Its GNSS Observations and Centimeter-Accurate Positioning. Sensors (Basel). 2022;22(5):1964. doi:10.3390/s22051964

Since this was published, more Galileo satellites have been deployed, and future firmware updates fixed an issue with Galileo satellite tracking.

No conflict of interest was declared.

You have to respect Garmin for their design, build quality and application of the QHA. As for real-world applications I can only think of surveying-type operations, to give you datums to work to.

But it would be far simpler and quicker to hire a calibrated instrument or a surveyor.

Makes me homesick for England! Good friends took me from Bristol to the dales in 1980.

My 9th cousin twice removed paid a visit in 2021.

https://www.examinerlive.co.uk/news/local-news/yorkshire-folk-love-joanna-lumley-19761045

In my days at Monash I went rock climbing at Hanging Rock

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=COJzQB_H5-0

Can't say I've been to the Yorkshire dales (yet) but I have been to the peak district a couple of times.

Even basically commandeered a replacement rail coach service in one instance. British rail couldn't organise themselves for toffee so I stepped up to the plate during one of my days off wanting to travel, got passengers to their respective coaches and annoyed the hi-viz twats so much they pulled a spare coach just to take me to the one obscure train stop I was going to just to get me to stop showing them up.

The coach driver then said he doubted they'd send another coach to pick me up from my stop and offered to take me on a tour of the peak district instead given no-one else was onboard, which I gracefully accepted. He was a local of the area. Didn't even have to get my feet wet!