Gut microbiota and colorectal cancer

+ What your doctor doesn't tell you about antibiotics and how to correct it

Last updated: 25th Feb. ‘24 (Further reading).

Reading time:

short story - novelette - novella - novel - PhD thesis - War and Peace - U.S. Tax Code

TL;DR: Look after your gut microbiota, and your microbiota will look after you. Try to cut down on alcohol, fat, sugar and carbs and increase your intake of fibre, prebiotics and probiotics for systemic benefits. These include reduced risk of cancer, a whole host of inflammation-related diseases and for mental health. If you suffer from IBD, colorectal cancer, poor immunity, are undergoing therapy or have completed a course of antibiotics then probiotics may be of significant benefit to you.

Also available with translator, 🇫🇷 🇪🇸 🇩🇪 🇯🇵 etc

Any extracts used in the following article are for non-commercial research and educational purposes only and may be subject to copyright from their respective owners.

Contents

The importance of a healthy gut microbiome for the efficacy of systemic chemotherapy

Aspirin for the prevention of CRC and the role of the microbiome

Cancer Research UK, microbiota research and probiotics recommendations

Can you take probiotics whilst undergoing chemo or radiotherapy?

Introduction

An adult's digestive tract is about 30’ (9m) long:

Colorectal cancer (CRC, also known as bowel cancer) is the third commonest cancer with nearly 2 million new cases per year worldwide and is the 2nd leading cause of cancer deaths.1 The economic cost per year of CRC is in excess of $2.7 trillion (ie treatment costs, sick pay and lost economic output).2

Less than 8% of cases are associated with genetic predisposition. Tumours are almost always adenocarcinoma (i.e. originate in the mucous glands). Loco-regional lymph nodes are usually involved before the cancer spreads more widely, although with rectal cancer the tumour may spread laterally into peri-rectal fat and lymph nodes.

Surgery is the primary means to achieve curative therapy. The aim is to be as minimally invasive as possible. Perioperative antibiotics (i.e. used around the time of surgery) and thromboembolic prophylaxis are viewed as mandatory to help reduce the risk of fatal complications. Radiotherapy is mainly used for palliative care but chemotherapy may be administered as a second-line adjuvant to try to reduce the risk of metastasis, occasionally as a first-line treatment for advanced cases.

Local recurrence happens most often with rectal cancer, with liver involvement and resection indicated, via a hepatobiliary specialist. The cure rate is up to 30% in some cases.3

Discussion

Latency period for CRC and colonoscopies

Neoplastic polyps are precursor lesions of CRC and are described as tubular and villous adenomas. Up to 95% of cases of sporadic CRC develop from these but the latency period before malignancy is quite long at 5 - 10 years.4

I wrote previously how our genes develop potentially cancerous somatic mutations throughout life and the genetic origins of these adenomas may lie in our childhood.5 Our immune system usually keeps them in check until we advance in years or become immunosuppressed.6

Early detection through routine colonoscopies of the over 45’s and removal prior to malignant transformation was thought to reduce the risk of CRC but in fact makes almost no difference to all-cause mortality due to the risk of complications in the elderly, who are most at risk of adenomas. The risk of tumour seeding is a factor7 and bowel perforation, bleeding, and cardiopulmonary complications increase with age.8

In 2022 Bretthauer et al conducted a randomized trial of 84,585 participants in Poland, Norway and Sweden. 28,220 were invited to undergo a single screening colonoscopy and 56,365 in the usual-care, unscreened group. During a 10 year follow-up 259 cases of CRC were diagnosed in the invited group and 622 in the unscreened group.

Screening was associated with a 0.98% risk of CRC vs 1.20% in the unscreened group, a relative risk reduction of 18%. The risk of death due to CRC was much closer between groups at 0.28% vs 0.31% and risk of death from any cause was virtually identical at 11.03% vs 11.04%, perhaps due to complications.

The number needed to screen to prevent one case of CRC was 455 (95% CI, 270 to 1429). The authors didn’t calculate numbers needed to prevent 1 death but looking at the data it would be multiples of this.9

The key take from this is that if you wish to significantly reduce your risk of death from CRC or its complications then undergoing a colonoscopy screening in itself is not enough. You need to consider addressing other lifestyle related factors too.

If you want to check your own theoretical lifetime risk of CRC you can fill in an anonymous questionnaire in a couple of minutes at this site:

Colorectal Cancer Risk Assessment Tool: Online Calculator

NHS guidance

It is always quite instructive to get the corporate view of diagnosis and treatment from the NHS (National Help-pharma Service). This gives you a good baseline for expectations and with fibromyalgia they didn’t disappoint.10

Who could forget their wilful ignorance of years of research into autoimmune involvement? And their dangerous drug-heavy recommendations were enough to cause any practitioner of holistic medicine to face palm.

They don’t know the cause, but they sure know the meds:

The NHS guide to bowel cancer isn’t much better.11 This time the blind spot is the importance of maintaining a healthy gut microbiota via diet and the potentially deleterious effects of antibiotic misuse:

Causes of bowel cancer

Who is more likely to get bowel cancer

It's not always known what causes bowel cancer, but it can be caused by genetic changes, lifestyle, and environmental factors.

Having certain health conditions can also make you more likely to get bowel cancer.

You may be more likely to get bowel cancer if:

you're over 50

you smoke

you're overweight

a close relative has had bowel cancer

you have inflammatory bowel disease, which includes Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis

you have small growths in your bowel called bowel polyps

you have Lynch Syndrome or familial adenomatous polyposis

As usual the treatments on offer amount to cut, poison or burn.

Minimising the risk of recurrence doesn’t warrant a mention (emphasis mine):

Main treatments for bowel cancer

The treatment you'll have for bowel cancer depends on:

the size of the cancer

if the cancer is in your colon or rectum, or both

if it has spread to other parts of your body

if the cancer has certain genetic changes

your age and general health

You may be offered a combination of treatments including surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and targeted medicines.

Your specialist treatment team will:

explain the treatments, the benefits and side effects

work with you to make a treatment plan that's best for you

help you to manage the side effects of treatment

If you have any questions or worries, you can talk to your specialist team.

Er, yeah thanks, that’s reassuring and really helping:

What happens if you've been told your cancer cannot be cured

If you've been diagnosed with advanced bowel cancer, it may be hard to treat and not possible to cure.

The aim of treatment will be to slow down the growth and spread of the cancer, to help with the symptoms, and help you live longer.

Finding out cancer cannot be cured can be very hard news to take in.

You'll be referred to a team of doctors and nurses called a symptom control team or palliative care team.

They will help you to manage your symptoms and make you feel more comfortable.

The palliative care team can also help you and your loved ones get any other support you need.

One part they couldn’t get wrong:

Main symptoms of bowel cancer

Symptoms of bowel cancer may include:

changes in your poo, such as having softer poo, diarrhoea or constipation that is not usual for you

needing to poo more or less often than usual for you

blood in your poo, which may look red or black

bleeding from your bottom

often feeling like you need to poo, even if you've just been to the toilet

tummy pain

a lump in your tummy

bloating

losing weight without trying

feeling very tired for no reason

Gut microbiota and CRC

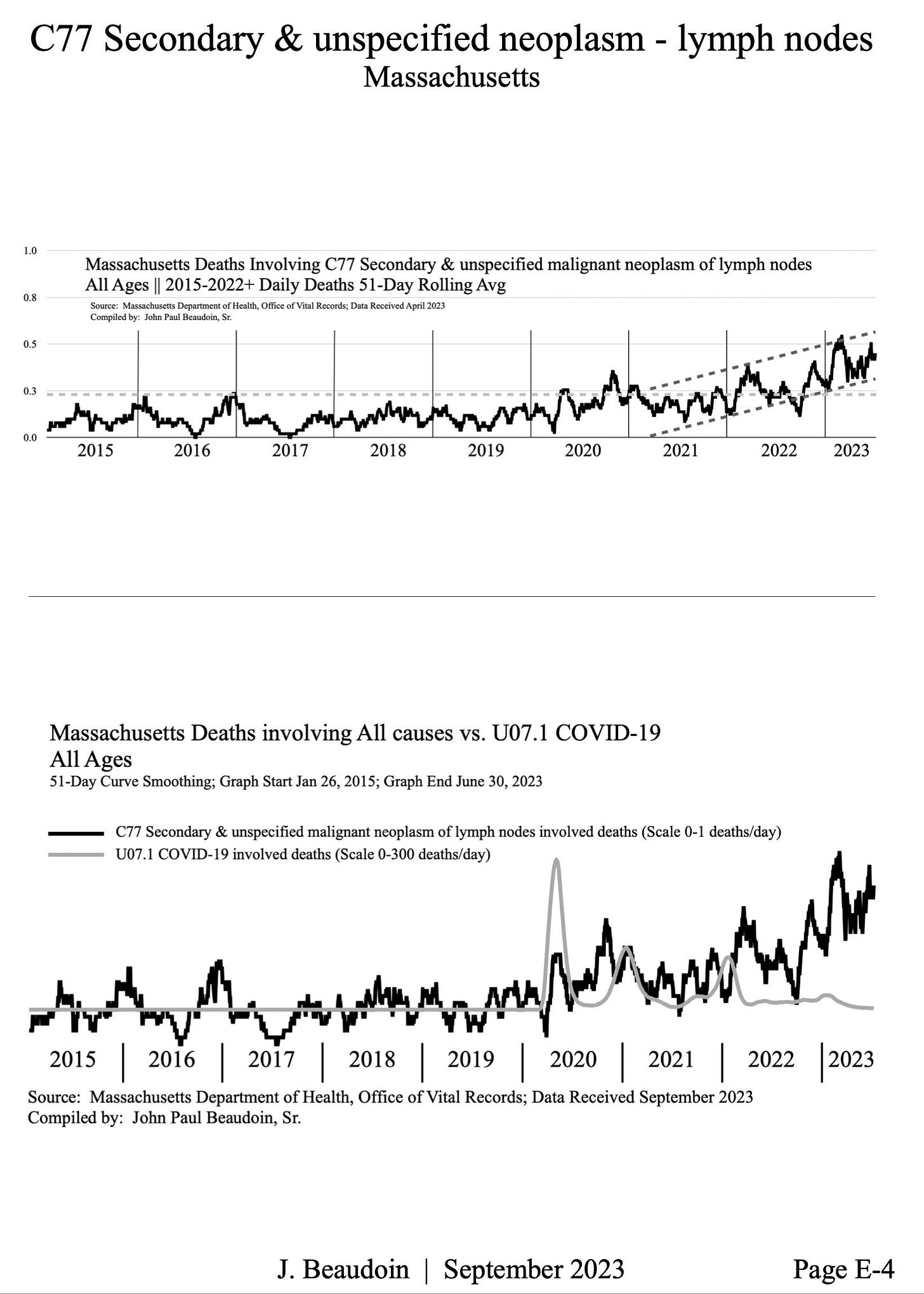

Cases of early-onset CRC (EOCRC, i.e. <50 year olds) are in a positive trend and this is due to a combination of factors. EOCRC differs from the more commonplace late-onset CRC (LOCRC) in many ways, including epidemiology, pathology, anatomically, biologically and metabolically.

EORC incidence is expected to grow by at least 140% by 2030, and rates have increased by at least 2% per year since 1994. Early data shows an inflection point in 2021 and rates are ratcheting up even more than this estimate implies.

Gut microbiota are at the crossroads of many contributory factors, including obesity, stress and poor diet.12 13

In 2020 Rebersek wrote a review called “Gut microbiome and its role in colorectal cancer”,14 and the research cited provides an excellent resource for the following discussion.

The top bubble is largely out of our immediate control but the bottom two not so much:

Gut microbiota: Also known as the gut microbiome, or gut flora are the microorganisms that live in the digestive tracts of animals. These include bacteria, archaea (single-celled organisms lacking a defined nucleus), fungi, and viruses.

Probiotics: Live microorganisms that are consumed to provide health benefits by restoring or improving gut microbiota.

Prebiotics: Non-digestible compounds in food that foster the growth or activity of beneficial microorganisms.

Antibiotic: A type of antimicrobial substance that is active against bacteria, either by killing or through growth inhibition.

The gastrointestinal (GI) tract is home to around 1014 microorganisms, comprising over 1000 species and 7000 different bacterial strains. The gut microbiome has 3 key functions, these are structural, protective and metabolic. It is important for nutrient and mineral absorption, enzyme synthesis, vitamin and amino acid creation, and for the synthesis of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs).

Key contributors to gut health, fermentation byproducts include butyrate and propionate. These help to maintain the integrity of epithelial barriers, to modulate the immune response and to help protect against pathogen invasion. You can get butyrate from butter (~3%) but most of it comes from the ‘good‘ bacteria in our gut.15

3 important axes connect gut health to the health of the host. Dysbiosis caused by alterations to the microbiota can disrupt both organ and brain function. Stress can also lead back to dysbiosis:

The metabolic axis. Digestion of fibre in the gut lumen and bile acids, fats and sugars contributes to the production of important metabolic products such as vitamins and neurotransmitters.

The neuroendocrine hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal gland (HPA) axis. This helps the body to respond to psychophysical stresses. Both the microbiota and vagus nerve are involved.

The axis between the brain and the intestinal microbiota. Gut health is linked to mental health, and communication is a two-way process. Signals from the brain affect motor, sensory and secretory function of the gut, and in turn intestinal microbiota can signal back to the brain via the intestinal nervous system.

A healthy gut microbiome (eubiosis) is characterized by a balance between bacterial diversity; proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines; immune cells and IgA antibody secretion; and an intact gut mucosal barrier.

If these are out of balance (dysbiosis) then the immune system may be compromised leading to a pro-tumour microbiome. What makes this worse is that dysbiosis can also limit the effectiveness of cancer treatments, such as chemotherapy or immunotherapy.

Gut microbiota associated with CRC differ from those of a healthy microbiome, and can act as a biomarker for the disease. More significant marker strains include: Bacteroides fragilis, Streptococcus gallolyticus, Enterococcus faecalis, Escherichia coli, Fusobacterium nucleatum, Parvimonas, Peptostreptococcus, Porphyromonas and Prevotella.

Colorectal carcinogenesis can be influenced via several mechanisms involving the microbiome:

Inflammation.

Regulation of immune response.

Production of harmful genotoxins and metabolites due to altered metabolism of dietary components.

“Driver bacteria” can be directly carcinogenic and “passenger bacteria” can be indirectly procarcinogenic. These tend to proliferate in the tumour associated microenvironment (TME) in an opportunistic manner.

Interactions between the microorganisms and the host can lead to the activation of pro-tumour signalling pathways. This can contribute to malignant transformation of pre-existing colorectal adenomas and progression of CRC.

Research has shown that different bacterial strains proliferate at different stages.

For instance, Atopobium parvulum and Actinomyces odontolyticus are only abundant with adenomas and intramuscular carcinomas, whereas Fusobacterium nucleatum and Solobacterium moorei are in high abundance only at later stages as CRC progresses to metastatic disease. The biome can also be different between left-sided and right-sided CRC, and need different treatment profiles.16

Tumour microbiomes are an essential component of a cancerous microenvironment. Different bacteria promote CRC progression through different mechanisms:

Fusobacterium nucleatum activates toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2) and inhibits tumour cell apoptosis (ie. programmed cell death) through oncogenic miRNA induced signalling pathways.

Peptostreptococcus produces metabolites that lead to a more acidic and hypoxic pro-tumour TME, as well as further enhancing bacterial colonization.

Escherichia coli can damage DNA as they are genotoxic. Genotoxins such as cyclomodulin cycle inhibiting factor (CIF) can damage the gut lining by blocking mitosis of epithelial cells and inducing apoptosis. Cytotoxic necrotizing factor 1 (CNF-1) can affect the cells actin cytoskeleton (the primary force-generating machinery in the cell), whilst colibactin induces double-strand breaks (DSBs) in DNA, which can lead to mutations and malignant transformation.

Some bacterial strains can secrete proteins called secretomes and metabolites called metabolomes that can establish interactions between the cancer cell and the host immune system. Pro-tumour secretomes include growth factors, proteases, cytokines and other proteins. Metabolomes include a sub-category of bacterial metabolites, the pro-tumorous oncometabolites. These can accumulate in cancer cells after being metabolized. Examples include L-2-hydroxyglutarate, succinate, fumarate, D-2-hydroxyglutarate and lactate. The latter acts as a fuel to serve cancer cell growth and progression. Butyrate, on the other hand suppresses both proinflammatory genes and tumour growth.

Effects of COVID-19 on the gut microbiome

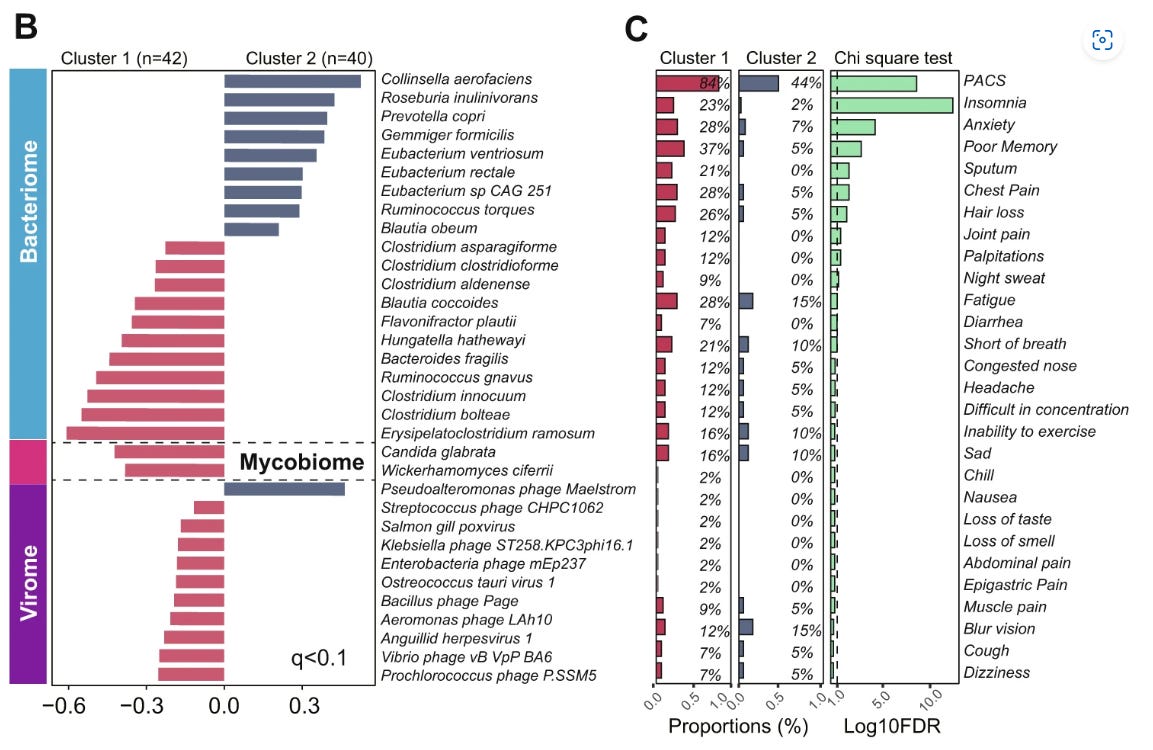

In 2022, Liu et al published an analysis of the gut microbiome of patients with severe COVID-19 or long COVID (= post-acute COVID, PACS or PASC) and again after a 6 month follow-up. Clusters 1 and 2 are robust ecological clusters.

Comorbidities and demographics were comparable between 1 and 2, although cluster 1 patients averaged 9.2 years older. 1 is significantly associated with severe COVID-19, PACS and an increase in opportunistic pathogenic bacteria.

The bacteria that proliferated the most in the less affected cluster 2 patients are not typically associated as drivers of CRC, but do increase the incidence and severity of rheumatoid arthritis (RA).

Both Collinsella aerofaciens17 and Prevotella copri18 have been found to be enriched in patients with both RA and pre-clinical RA. Bacteria like these can increase gut permeability due to decreased expression of tight junction proteins and through production of metabolites that destroy collagen by intestinal epithelial cells (IECs).19

I haven’t gone through all of these, please add comments below, but an outlier I spotted is the myovirus Pseudoalteromonas phage Maelstrom. A bacteriophage infects and replicates in bacteria and archaea, but Pseudoalteromonas is a cold-active marine phage (ie infects and replicates at ≤4 °C).

Its normally more at home in the uppermost layers of ocean water, in polar seas and has been found in polar continental shelf sentiments in the Arctic.20

I’m not a specialist in phages so cannot comment on whether its presence in humans is unusual or what bacteria in our microbiome it infects!

Another cancer pathway linked to COVID-19, long COVID and gut dysbiosis is due to impaired tryptophan absorption and activation of the immune suppressing, pro-tumour kynurenine pathway.21 Tryptophan is an essential amino acid and it can only be obtained through diet from foods including meat, dairy and seeds. You can also supplement with it.

One theory is that the virus binds to abundant angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptors in the gut, disrupting expression of ACE2 and, downstream of that, a neutral amino acid transporter in the intestine called B0AT1, thus impeding absorption of tryptophan. L-tryptophan is also the main precursor of neurotransmitters such as serotonin, which may also contribute to depression and anxiety of long COVID.22

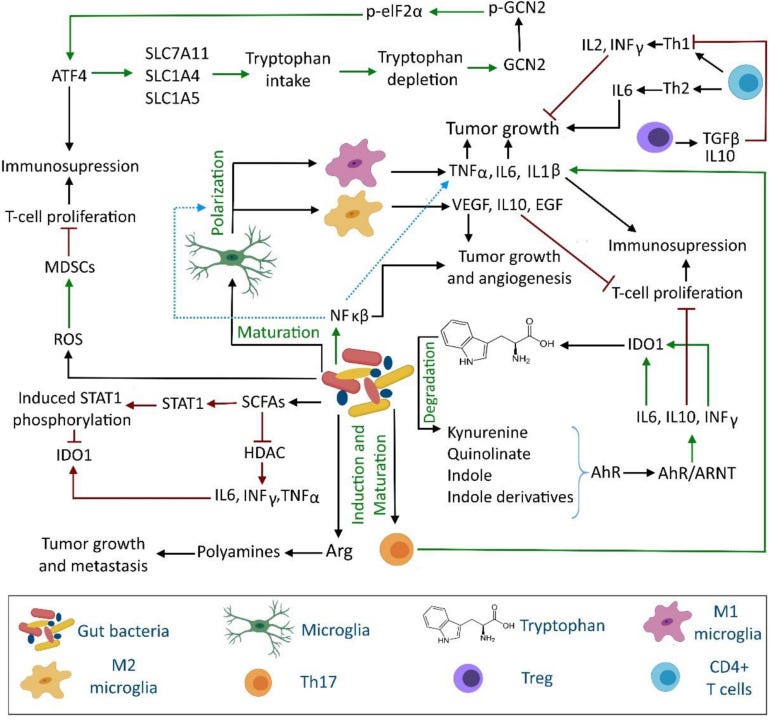

Denhhaghi et al (2020)23 reviewed how gut microbiota, as part of the gut-microbiota-brain-cancer axis, can promote brain tumour pathways via the kynurenine pathway.

Its a complex 2-way process with many signalling pathways, feedback and involvement of bacterial debris and antigens such as lipopolysaccharides (LPS) and amyloid protein. You will note immunosuppression and tumour promotion at multiple points:24

And in 2021, Wyatt & Greathouse reviewed how disrupted tryptophan, kynurenine and indole pathways can lead to T cell inactivation and increase the pathogenesis of CRC, other cancers and diseases.25

The warning being given here is that even less severe COVID may contribute to increased future incidences of cancers, long-COVID and autoimmune diseases such as RA.

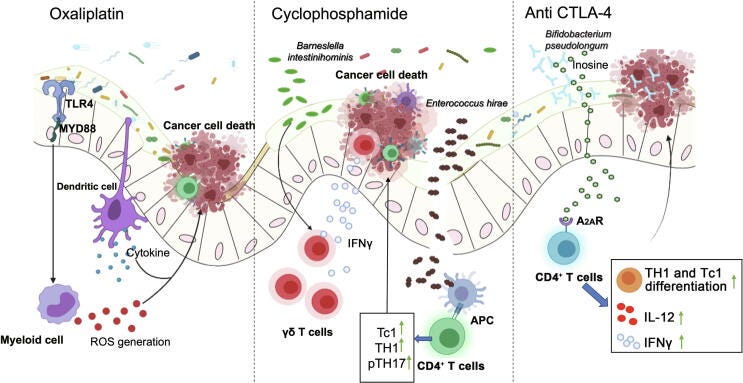

The importance of a healthy gut microbiome for the efficacy of systemic chemotherapy

There has been a lot of research into this and provided you are not severely immunosuppressed then probiotics may improve the efficacy of chemo and improve outcomes, including life expectancy and reduced risk of recurrence.

The gut microbiome modulates the metabolism and pharmacokinetics of chemotherapeutics, as well as their antitumour activity and toxicity. The response to a range of agents prescribed to treat metastatic CRC can be enhanced, including irinotecan, oxaliplatin and 5-flurouracil.

Don’t expect your doctor to tell you this though. This is what our “friends” at the NHS have to say about probiotics (emphasis mine):

Probiotics are thought to help restore the natural balance of bacteria in your gut (including your stomach and intestines) when it's been disrupted by an illness or treatment.

There's some evidence that probiotics may be helpful in some cases, such as helping to ease some symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS).

But there's little evidence to support many health claims made about them. For example, there's no evidence to suggest that probiotics can help treat eczema.

…Probiotics are generally classed as food rather than medicine, which means they don't go through the rigorous testing medicines do.

Because of the way probiotics are regulated, we can't always be sure that:

the product actually contains the bacteria stated on the food label

the product contains enough bacteria to have an effect

the bacteria are able to survive long enough to reach your gut

There are many different types of probiotics that may have different effects on the body, and little is known about which types are best.

You may find a particular type of probiotic helps with one problem. But this doesn't mean it'll help other problems, or that other types of probiotic will work just as well.

And there's likely to be a huge difference between the pharmaceutical-grade probiotics that show promise in clinical trials and the yoghurts and supplements sold in shops.

From: “Probiotics”

The full article doesn’t even mention the C word let alone chemotherapy. They steer well clear of any positive research into shop-sold probiotics and that many of these contain just as many active colony-forming units (CFU’s) as those used in clinical trials. More on that later.

The other side to the microbiome is that it can mediate resistance to chemotherapy or increase its toxicity, such as with irinotecan. Irinotecan produces the active metabolite SN-38, which causes irinotecan-induced diarrhoea.

The most prescribed agent for CRC is an antimetabolite drug called fluoropyrimidine. The makeup of the gut microbiome can have a profound effect on its metabolism and pharmacodynamics. Drug efficacy can be antagonised by the inhibition of bacterial ribonucleotide metabolism (i.e. bacterial RNA metabolism), whereas it can be enhanced by the inhibition of deoxyribonucleotide metabolism (i.e. human DNA metabolism).

Dietary nutrients such as pyrimidines and vitamin B6 (pyridoxine) can affect the efficacy of the fluoropyrimidine 5-Fluorouracil (5-FU) by disrupting bacterial folate metabolism.

Unlike with eukaryotes (such as ourselves), E. coli is capable of synthesizing PLP, the active form of vitamin B6, via both de novo and salvage biosynthetic pathways. Nucleotide salvage pathways recover bases and nucleosides from RNA and DNA degradation or from exogenous sources and convert them back to pyrimidines and purine nucleotides. Quite a useful trick.26

Indeed a study which tested the effects of 5-FU on the nematode C. elegans found that B6 from E. coli was essential for it to work.27

An excellent dietary source of both purine and pyrimidine is baker’s yeast. Animal muscle (i.e. meats such as pork, beef and chicken, as well as fish and shrimps) is rich in ATP and is a great source of purine nucleotides.28

In case you were wondering about supplementation and systemic effects…

In 2022, 27 patients with advanced breast cancer were given high doses (1000-3000 mg/day) of pyridoxal 5’-phosphate, the cofactor of vitamin B6.29

This was given to potentiate the cytotoxicity in cancer cells of drugs given alongside, including 5-fluorouracil (FUra), folinic acid (FA) and other standard chemotherapeutic agents via pyridoxine (B6).

In Group I there were 18 patients, 12 with easier-to-treat tumours that did not overexpress HER2. They received a range of agents but no B6 cofactor. 3 of these had complete regression (CR) and 9 had 62-98% partial regression (PR).

Of the 6 patients in Group II with overexpressed tumour HER2, 4 had CRs and 2 had PRs with 98% reduction. They had been given B6 cofactor in addition to a range of agents. These are excellent outcomes!

There were 9 patients in Group III and they all had prior chemotherapy for stage IV breast cancer diagnosed 1.5 to 25 years (mean: 8.4 years) earlier, and were given the B6 cofactor.

7 were measurable and of these 2 attained CRs and 5 had 81-94% PR’s. The median time to response was 3.4 months and there was no unexpected toxicity.

They concluded (emphasis mine):

…This pilot study suggests that high-dose vitamin B6 enhances antitumor potency of regimens comprising FUra and FA.

…The great magnitude of antitumor responses which were rapidly attained by patients with breast carcinoma who carried great tumor burden in most cases, suggest that addition of vitamin B6 in high dose strongly enhances the antitumor activity of combination regimens comprising FUra and FA. This antitumor potency may predict for favorable long-term outcomes as reported from studies of patients with colorectal carcinoma60, and breast carcinoma61 in advanced stages that attained early tumor shrinkage and deep antitumor responses under induction treatment.

The remarkable antitumor activity observed in the present pilot study may represent the difference with that reported elsewhere in trials using combination regimens administered in their standard form.

From: “Pharmacologic modulation of 5-fluorouracil by folinic acid and pyridoxine for treatment of patients with advanced breast carcinoma“ (2022)

Effects of antibiotics

Liu et al (2022) reviewed the literature investigating the effects of antibiotics on the gut microbiota and cancer.30 Outcomes depend on both the type of cancer and antibiotic treatment used, as some antibiotics are used in chemotherapy for their antitumour properties. These include dactinomycin, adriamycin, bleomycin, mithramycin, and mitomycin-C.31

On the other hand, platinum containing agents such as oxaliplatin and cisplatin are used as standard first line therapy for many cancers, including advanced CRC.32 These have their drawbacks though, due to tumour resistance33 and a study using mice found that when treated with an antibiotic cocktail (ABX, of vancomycin, imipenem, and neomycin) 3 weeks before tumour inoculation led to the reduction of expression of pro-inflammatory genes induced by oxaliplatin. This is unfortunate as it is responsible for its main anti-tumour effects. Oops.

And it’s worse than that. Genes relating to immune cell activation, differentiation and function of monocytes is impaired, as well as oxaliplatin mediated reactive oxygen species (ROS) production by tumour infiltrating immune cells.34

Another mouse study found that the effects of the chemotherapeutic CTX on subcutaneous transplantable tumours was “dramatically decreased” after treatments with broad-spectrum antibiotics and the gram-positive bacteria treating vancomycin.

Part of the efficacy of CTX is due to it promoting the translocation of Gram-positive bacteria, including Enterococcus hirae or Lactobacillus johnsonii into secondary lymph nodes. Once there the bacteria stimulate production of anti-tumour CD4+ T cells by triggering differentiation into TH1 and TH17 cells.35

Is chemo doing the bulk of the work or is it down to our microbiota?

Aspirin for the prevention of CRC and the role of the microbiome

A meta-analysis by Bosetti et al (2020)36 found that regular aspirin use is associated with significantly reduced risk of the following colorectal and digestive tract cancers.

1.0 = pooled relative risk (RR) of non-use:

CRC: (RR = 0.73, 95% confidence interval (CI) = 0.69–0.78, 45 studies)

“For colorectal cancer, an aspirin dose between 75 and 100 mg/day conveys a risk reduction of 10%, and a dose of 325 mg/day of 35%.”

Squamous-cell esophageal cancer: (RR = 0.67, 95% CI = 0.57–0.79, 13 studies)

Adenocarcinoma of the esophagus and gastric cardia: (RR = 0.61, 95% CI = 0.49–0.77, 10 studies)

Stomach cancer: (RR = 0.64, 95% CI = 0.51–0.82, 14 studies)

Hepato-biliary tract cancer: (RR = 0.62, 95% CI = 0.44–0.86, five studies)

Pancreatic cancer: (RR = 0.78, 95% CI = 0.68–0.89, 15 studies)

The Liu et al review of related research showed that your microbiome can affect the antitumour effects of aspirin, and vice versa. Lactobacillus sphaericus is the main microbe responsible for inhibiting its effects by degrading it and its active metabolite salicylic acid.

In contrast, aspirin treatment can have probiotic effects, by leading to the accumulation of CRC protective bacteria including B. pseudolongum, Bifidobacterium breve, Bifidobacterium animalis, Lactobacillus reuteri, Lactobacillus gasseri and L. johnsonii.

Another study found that aspirin treated transgenic CRC-prone mice had reduced tumour numbers and loads:

“Our results suggest that low‐dose aspirin represents an effective antitumor agent in the context of colon tumorigenesis primarily due to its well‐established cyclooxygenase inhibition effects.”37

Cancer Research UK, microbiota research and probiotics recommendations

A Midwestern Doctor just posted an excellent article on health charities and how, too often, the crock is all sauce and no beans:

CRUK has sponsored some research into this area, including the £20m OPTIMISTICC 5 year Cancer Grand Challenges from 2019. But as ever, the aims are high but changes to current practice never seem to result.

And why don’t they cite any of the extensive research and clinical trials that have already been conducted over the last few decades, only a few of which I referenced here?

Do we really need yet more expensive long term studies?

As for probiotics they vehemently dissuade cancer patients from taking them. In that case, why bother with the CRC microbiome research in the first place?

Avoid supplements, food and drinks containing probiotics such as bio-yogurts. These contain live bacteria and although generally considered safe, need to be use with caution during chemotherapy when your immune system may be weakened

From: “Social life, alcohol and other activities during chemotherapy”

Caution, yes, but nothing proactive. This is all the advice on probiotics I can find on their site. Which is unfortunate given their huge systemic contributions to cancer prevention and outcomes from our microbiota, including on chemotherapy, and there is nothing novel about this.

The Willie Sutton Rule, or Sutton’s Law, states that we should focus on where the money is, which in the world of business means the most profitable activities, rather than wasting valuable time on less lucrative ones. Choose whatever is most likely to produce the highest yield.

https://marketbusinessnews.com/financial-glossary/willie-sutton-rule-definition-meaning/

Hence “cut, poison and burn” cancer therapies remain their mainstay.

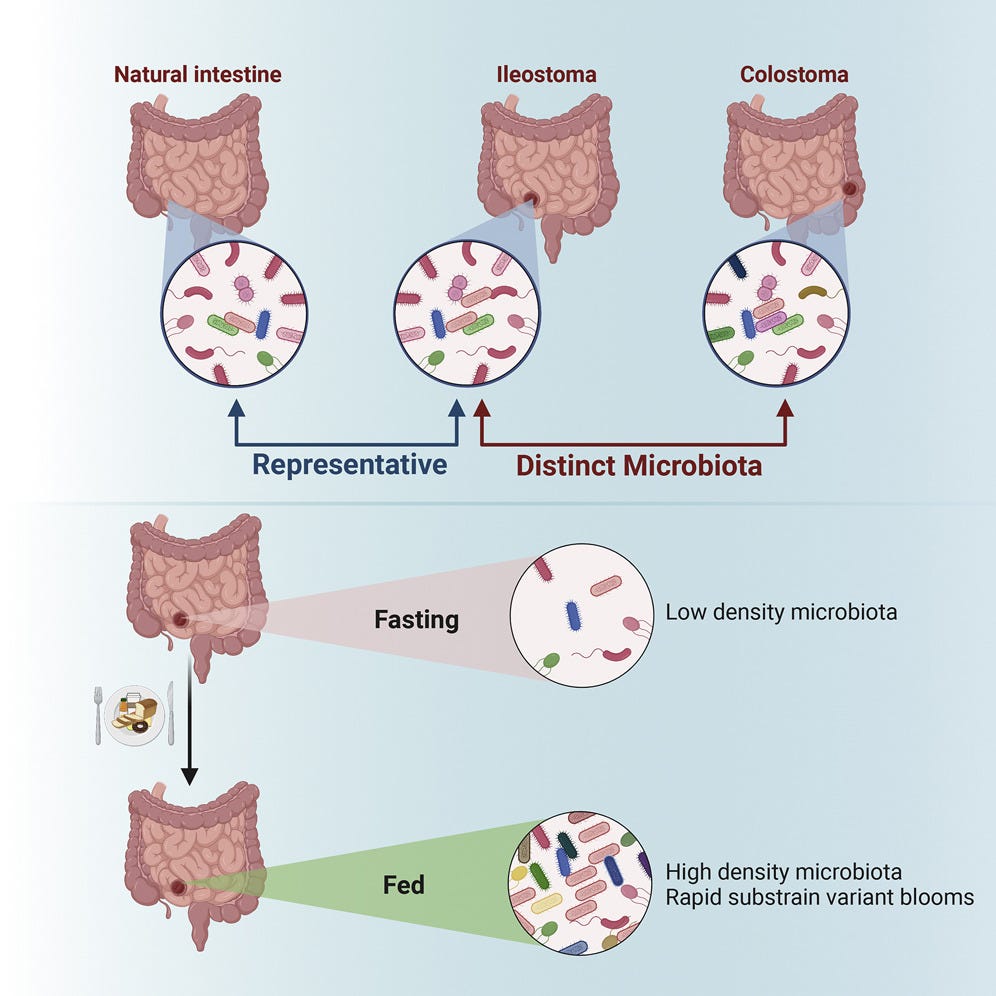

Microbiota in patients with a stoma

From Japan (2022), Sakai et al compared faecal microbiota in patients with and without a stoma.38 In the stoma patients they found that the abundance of Alistipes, Akkermansia, Intestinimonas, and methane-producing archaea decreased. They also found that gene expression function for production of methane and short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) was underrepresented. What this means is that these patients have a reduced abundance of microbes favourable for cancer immunotherapy.

Reduced transit time due to foreshortening of the GI tract may have been a factor, impairing microbial alpha diversity.

Nb. There was a long list of conflict of interest declarations.

In another study, Nagata et al (2019) found that bowel preparation and cleansing for surgery caused the gut microbiome and 32 metabolites to be significantly changed before and immediately after the prep, and needed 14 days to recover.

Other studies have shown long lasting effects on gut microbiota, especially reduced Lactobacillaceae abundance for at least a month.39 Lactobacillus contributes to restoration of immunity and has anti-CRC properties.40

In contrast ileal (small intestine) stoma microbiotas can be highly dynamic, starting to recover within hours of surgery:

This randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled study of the effects of probiotics on symptoms and recovery after colon surgery may have saved CRUK some time and money and avoids re-inventing the wheel:

Park et al (2020) gave 29 patients probiotics a week before and four weeks after undergoing anterior sigmoid colon cancer resection.41 31 of the 60 received the placebo.

Participants received either 2g of probiotic powder or 2g of placebo powder (350 mg of xylooligosaccharides and 36 mg of fructooligosaccharides as prebiotics without probiotic strains). I would question whether even the “placebo” would have beneficial effects as it contained prebiotics? No conflicts of interest were declared.

The probiotic powder contained three strains: Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis HY8002 (1 × 108 cfu), Lactobacillus casei HY2782 (5 × 107 cfu), and Lactobacillus plantarum HY7712 (5 × 107 cfu).

Bacteria were analysed and grouped as Set I (probiotic, anti-cancer and symptom reducing) and Set II (colon cancer-associated).

Set I anterior resection syndrome (ARS) scores showed a significant improving trend, particularly with flatus control and significantly reduced zonulin levels (an enterotoxin that is a biomarker for intestinal permeability and is associated with autoimmune diseases and cancer).42

As Bifidobacterium levels increased, zonulin levels decreased in the probiotic group.

Probiotics led to increases in Set I bacteria, decreases in Set II and led to modified postoperative changes in microbiota and inflammatory markers, together with reduced postoperative bowel discomfort.

And in 2021, Pitsillides et al conducted systematic reviews and meta-analyses to compare perioperative care outcomes of CRC patients given antibiotics with or without probiotics.43

Although heterogeneity was observed in outcomes (i.e. results weren’t consistent) analysis revealed a trend towards lower rates of postoperative infectious and non-infectious complications with probiotics vs the placebo.

The three most commonly used probiotic species in the studies were: Lactobacillus acidophilus, Bifidobacterium longum, and L. plantarum.

Prebiotics and probiotics

Wu & Wu (2012) discussed human practices that can influence the composition of your microbiota.44 It might be worth reviewing your diet before reaching for the pill jar or the probiotic yoghurt pot:

A study using germ free (GF) mice found that your microbiome can be shifted in just one day by changing from a low-fat, plant polysaccharide-rich diet to a high-fat, high-sugar diet.45

Another study compared the microbiome of African children, whose ‘healthy’ diet was rich in fibre, starch and plant polysaccharides and low in fat and animal protein to European children.46 These kids lived on a familiar diet (!) that is high in sugar, starch and fat and low in fibre.

The microbiota of the African children showed a significant depletion in carbohydrate-associated Firmicutes - and an increase in polysaccharide-associated Bacteroidetes. Plant polysaccharide digestion-promoting Prevotella and Xylanibacter were detected, but these were completely absent from the European children.

The African children also had significantly higher levels of anti-inflammatory molecules such as short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs).

Using a nonobese diabetic (NOD) mouse model, researchers found that if they were fed a special soy-based diet then they had a significantly lower incidence of diabetes.47 One of the reasons for this was a reduction in colonic pro-inflammatory cytokines, including oncogenic IL-17 and IL-23.

Antibiotics, as discussed earlier, vaccinations and hygiene practices can all alter the composition of your gut microbiota. Antibiotic use was associated with the reduction of Bacteroides and Bifidobacterium, outgrowths of yeasts such as Candida albicans and proliferation of pathogenic bacteria including Campylobacter, Streptococcus and Leuconostoc.48

Even formula-feeding infants vs breast fed is associated with colonization of pathogenic type Staphylococci, E. coli, C. difficile, Bacteroides, Atopobium and Lactobacilli and also with a delayed colonization of Bifidobacterium species.49

Formula-feeding and caesarean section may well increase your risk of developing autoimmune diseases and allergies in later life, including asthma, as the mother’s microbiota is less likely to be acquired due to the newborn not passing through the birth canal.50

Prebiotic foods contain food components that are indigestible to us but which are an important food source for beneficial bacteria. These get fermented in the GI tract and produce useful metabolites we discussed earlier. They have anti-inflammatory and anti-cancer properties and include SCFAs, which intestinal cells CAN use as an energy source. The low pH, acidic environment created is also beneficial for probiotic bacteria, whilst inhibiting less beneficial ones.

Examples of prebiotics, or prebiotic-containing foods include:51 52

Psyllium.

Raw garlic.

Raw or cooked onion.

Artichokes.

Raw leafy greens: dandelion, leak, endive, radicchio (chicory).

Black salsify.

Almonds.

Bananas.

Whole grain wheat.

Whole grain corn.

Whole grain rye and barley.

Flax seeds.

Soy.

Cabbage.

Jicama.

Peas.

Eggplant.

Asparagus.

Agave nectar or honey.

Oats.

Beans.

Probiotic foods include:

Natural yoghurt, which may have probiotic cultures added.

Probiotic capsules, liquids, powders, gummies or tablets.

Kefir, from milk fermented with special cultures.

You should aim to get a balance of prebiotics and probiotics in your diet.

CFU’s

Probiotics are measured in colony forming units (CFUs), which indicate the number of viable microbial cells. This may be written on the product label or be available on the manufacturers’ website and is more indicative than the weight of microorganisms alone, as these may be counted whether they are dead or not.

Many probiotics contain 1-10 billion CFU per dose, but 50 billion is not unusual.53 1 billion CFU may be written as 1 x 109 CFU, but higher is not necessarily better. 1 x 107 CFU has been shown to be effective in several studies and manufacturers often use very high concentrations to allow for degradation and losses in the stomach. CFU may confusingly be given per ml, per dose, per gram or per bottle.

1 x 109 CFU per dose appears to be a useful reference, although there is nothing set in stone about this as there are so many variables involved.

A useful website for comparing commercially available products is by NatMed, including whether the product has been rated as a treatment.

If we take a typical “Activia” yoghurt pot weighing 125g and there are 100 million+ live bacteria per gram, then this equates to 1.25 x 1010 CFU:

Storage and degradation

- Probiotic yoghurts

Scharl et al (2011) investigated whether the interruption to cold chain of probiotic yoghurt used to treat ulcerative colitis affected the number of probiotic bacteria.54

They took three commonly available probiotic yoghurts and either kept them at 4°C or put them at room temperature (RT) for 6h or 24h before incubating an aliquot for 48h at 37°C and counting the number of CFUs.

The first probiotic yoghurt contained Lactobacillus johnsonii and the CFU decreased significantly after only 6h at RT and this was even more pronounced after 24h.

The second contained Lactobacillus GG and results were similar to the first:

The third contained Lactobacillus acidophilus and the outcome was even worse: after only 6h the CFU had already fallen to 53.8%, and by 24h just a quarter of the original live bacteria were left:

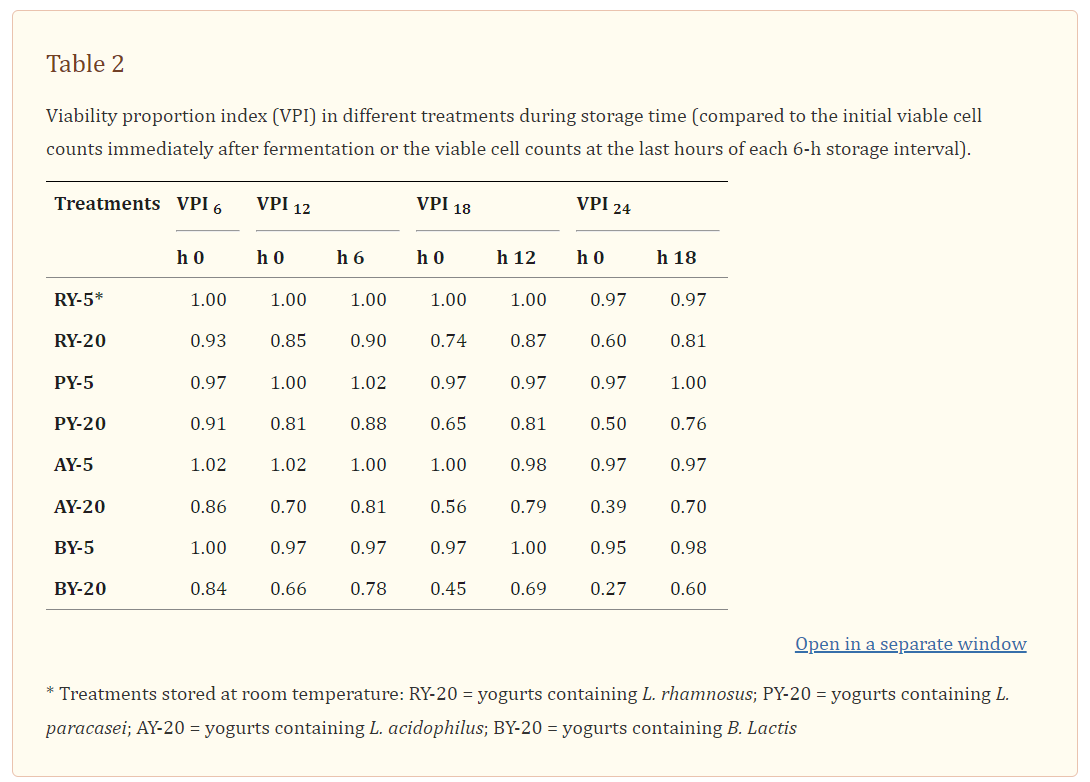

Another study from 2013 by Ferdousi et al investigated the viability of probiotic strains in milk inoculated with yogurt bacteria culture (Streptococcus thermophilus and Lactobacillus delbrueckii ssp. bulgaricus) and a single probiotic culture (L. acidophilus LA-5 or Bifidobacterium lactis Bb- 12 or L. rhamnosus HN001 or L. paracasei Lpc-37).55 Probiotic yoghurt CFU’s were counted for every 6h of storage up to 24h.

They also found that a dramatic loss of viability occurred at RT when compared to refrigerated storage:

Although some strains are less sensitive to temperature than others (after all, our gut is at 37°C ) advice is to keep them cool until you consume them.

As to why some strains are quite happy at body temperature yet degrade quickly at room temperature the authors discuss this:

"Considerable loss in viability of probiotics in room temperature could be attributed to increasing cell metabolism and death at higher temperatures (compared to refrigerated storage) as well as to the enhanced antagonistic impact of yogurt bacteria (especially L. delbrueckii ssp. bulgaricus) on probiotic bacteria."

The good thing is that, the above notwithstanding, meta-analyses of studies shows that enough do reach their target and make a positive difference.

- Fermented milk/Kefir

Deserving it’s own Substack, milk Kefir (pronounced keh-FEER) is a slightly carbonated fermented milk drink similar to yoghurt or buttermilk. It is thought to have originated in the Caucasus Mountains around 2000 years ago, as fermentation is a longstanding natural method of preservation.

The name is derived from the Turkish word for ‘feeling good’, “Keif”. Most relevant to storage life and CFUs is that milk is fermented with kefir grains overnight for about 24 hours at room temperature.

Not only are many of the strains quite proliferative at room temperature you may need to put kefir in the fridge just to slow fermentation. It can be stored at room temperature for around 3-5 days or in the fridge for 7-10 days once fermented, but it tastes better when chilled. You can leave it much longer but acidity increases with age. It also contains a small amount of alcohol which builds the longer its been fermented (0.08-2.0%).

Shop bought kefir yoghurts are not made by the traditional method using kefir grains but the same way yoghurt is and they rarely contain yeast. For example, “Yeo Valley Organic Kefir Yoghurt” is made with 14 different live cultures and needs to be stored in the refrigerator (not an endorsement).

Advantages of traditional kefir over probiotic supplements are that in addition to probiotic microorganisms it also contains enzymes, pre-digested nutrients, amino acids, vitamins, minerals and is a source of calories. The consumption of lactose by its bacteria and yeast also makes it more suitable for the lactose intolerant.

Research has identified a very wide range of microorganisms in comparison to the other probiotics discussed in this Substack. Indeed there are so many that you should take a small amount - between a spoonful and a 1/4 pint for a week or so - until you know you are free of side effects and have built up a tolerance.

The biodiversity of species, often acting in synergy, makes conducting reproducible research or clinical trials quite challenging due to heterogeneity.56

LACTOBACILLI:

Lactobacillus acidophilus

Lb. brevis [Possibly now Lb. kefiri]

Lb. casei subsp. casei

Lb. casei subsp. rhamnosus

Lb. paracasei subsp. paracasei

Lb. fermentum

Lb. cellobiosus

Lb. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus

Lb. delbrueckii subsp. lactis

Lb. fructivorans

Lb. helveticus subsp. lactis

Lb. hilgardii

Lb. helveticus

Lb. kefiri

Lb. kefiranofaciens subsp. kefirgranum

Lb. kefiranofaciens subsp. kefiranofaciens

Lb. parakefiri

Lb. plantarum

STREPTOCOCCI/LACTOCOCCI:

Streptococcus thermophilus

St. paracitrovorus ^

Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis

Lc. lactis subsp. lactis biovar. diacetylactis

Lc. lactis subsp. cremoris

Enterococcus durans

Leuconostoc mesenteroides subsp. cremoris

Leuc. mesenteroides subsp. mesenteroides

Leuc. dextranicum ^

YEASTS:

Dekkera anomala t/ Brettanomyces anomalus a

Kluyveromyces marxianus t/ Candida kefyr a#

Pichia fermentans t/ C. firmetaria a

Yarrowia lipolytica t/ C. lipolytica a

Debaryomyces hansenii t/ C. famata a#

Deb. [Schwanniomyces] occidentalis

Issatchenkia orientalis t/ C. krusei a

Galactomyces geotrichum t/ Geotrichum candidum a

C. friedrichii

C. rancens

C. tenuis

C. humilis

C. inconspicua

C. maris

Cryptococcus humicolus

Kluyveromyces lactis var. lactis #

Kluyv. bulgaricus

Kluyv. lodderae

Saccharomyces cerevisiae #

Sacc. subsp. torulopsis holmii

Sacc. pastorianus

Sacc. humaticus

Sacc. unisporus

Sacc. exiguus

Sacc. turicensis sp. nov

Torulaspora delbrueckii t

* Zygosaccharomyces rouxii

Microbial Composition of Kefir at End of Fermentation [colony forming units/ml] **

Lactococci : 1,000,000,000

Leuconostocs : 100,000,000

Lactobacilli : 5,000,000

Yeast : 1,000,000

Acetobacter : 100,000

Sources:

MILK KEFIR FAQ: INTRODUCTION & BASICS

U of A researchers develop healthier recipe for store-bought kefir

Yeo Valley Organic Natural Kefir Yoghurt

Kefir and Cancer: A Systematic Review of Literatures

Anticancer Activity of Kefir on Glioblastoma Cancer Cell as a New Treatment

Effects of probiotics on GI diseases

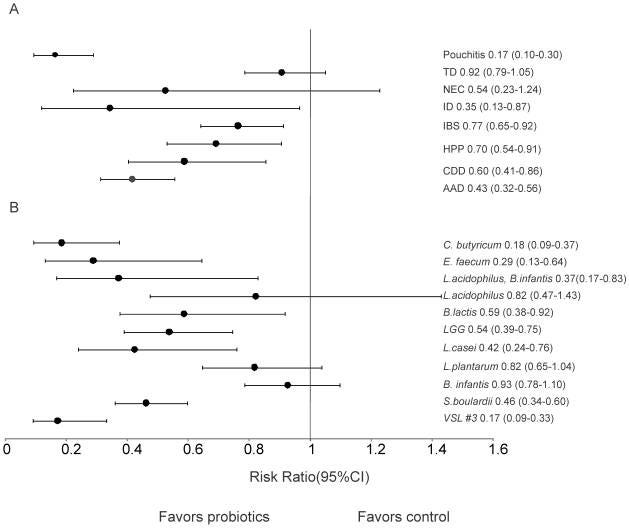

Another study that would save CRUK a lot of work was a meta-analysis on the effects of probiotics on specific gastrointestinal diseases by Ritchie & Romanuk, back in 2012.57 They included randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that used probiotics to treat or prevent:

Pouchitis (nothing to do with your pet dog’s upset tummy, its “inflammation that occurs in the lining of a pouch created during surgery to treat ulcerative colitis or certain other diseases.”58)

Infectious diarrhea.

Irritable Bowel Syndrome.

Helicobacter pylori.

Clostridium difficile Disease.

Antibiotic Associated Diarrhea.

Traveler's Diarrhea.

Necrotizing Enterocolitis.

Probiotics significantly reduced the relative risk of 6 of the 8 GI diseases by 42% or 0.58 (95% (CI) 0.51–0.65).

Efficacy against amoeboid Traveler's Diarrhea and Necrotizing Enterocolitis was not detected.

Of the 11 strains used in the probiotics, all but Lactobacillus acidophilus, Lactobacillus plantarum, and Bifidobacterium infantis showed significant positive effects, left is best:

Efficacy was not statistically different across all the age groups. And variations in dose (ranging from 1–5×1010 CFU/day; 1–5.5×106, 107, 108 CFU/day and 1–9×109 CFU/day) didn’t significantly affect results either, including single dosing.

What did affect results was duration of treatment: 1-2 weeks; 3-4 weeks; 5-8 weeks and 9-240 weeks. The latter group showed significantly higher efficacy than the 3–4 week group.

Curiously the number of species included in the probiotic didn’t affect outcomes either, and I found this in another paper too - the effects on gut microbiota diversity were the same from a single strain as multiple.

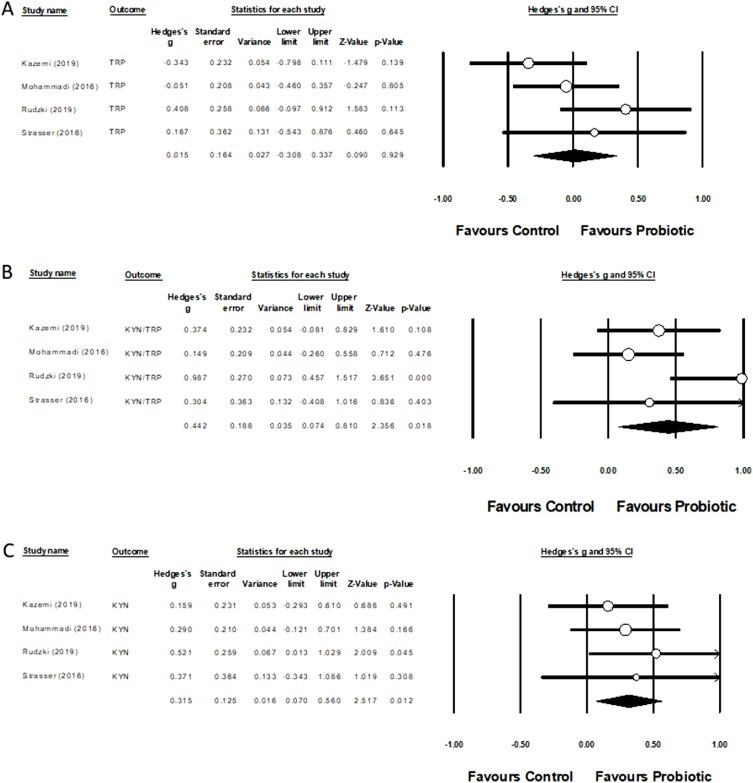

Probiotics and the kynurenine pathway (KP)

In 2021, Purton et al conducted a systematic review of 13 studies investigating 12 kynurenine metabolites and the effects of prebiotics and probiotics.59

Of the 12 studies involving probiotics (9 RCTs, 3 single arm), CFU’s ranged from 10 million to 1.8 trillion; microbial genera used included Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium, Streptococcus, Lactococcus and Enterococcus; probiotics were in carriers of yoghurt, fermented milk, capsules or powder.

Prebiotics in the other 2 studies consisted of 10 g of water soluble resistant dextrin in one and 5 g of orally dispersible galactooligosaccharide in the other.

Of the 2 prebiotic and 12 probiotic interventions, 11 reported an effect on 1 or more metabolites. Meta-analysis showed that probiotics affect kynurenine and the kynurenine:tryptophan ratio.

Preliminary evidence indicated that metabolic activity in the KP can be modulated by probiotics. However, evidence was limited as to the effects of prebiotics on metabolism of the KP. Right is best:

Probiotic Lactobacillus casei Shirota (LcS)

This isn’t an endorsement of any particular product but you may ask why this particular strain is favoured in some probiotics?

In 2022 Yan et al analysed the effects of LcS on the gut microbiome, metabolome (metabolite make-up) and transcriptome (protein encoding RNA transcripts).60 They found that it lowered the ratio of Firmicutes to Bacteroidetes, enriched beneficial metabolites and improved liver function. This makes LcS a prospective treatment for acute liver injury (ALI).

And in 2016 Kato-Kataoka et al conducted a novel, double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial to investigate the effects of LcS on abdominal dysfunction in healthy medical students exposed to academic stress.61

For 8 weeks before the exam 23 students consumed L. casei strain Shirota-fermented milk and 24 were given a placebo milk daily. They were assessed for a range of factors including abdominal symptoms, psychophysical state, salivary stress markers, gene expression changes in peripheral blood leukocytes and composition of the gut microbiota.

In the LcS group gene expression in leukocytes associated with abdominal dysfunction were suppressed more than 2-fold than in the placebo group. This was also reflected by significantly reduced abdominal dysfunction symptoms when compared to the placebo group.

Salivary cortisol (i.e. fight-or-flight) was increased only in the placebo group.

Analysis of the microbiota showed that despite being only one strain LcS helps to preserve diversity in response to stressful situations - the LcS group had a significantly higher number of species (i.e. a marker of the alpha-diversity index) and a significantly lower percentage of Bacteroidaceae (potentially abscess forming gut bacteria62).

Can you take probiotics whilst undergoing chemo or radiotherapy?

CRUK: “Avoid supplements, food and drinks containing probiotics such as bio-yogurts.”.

But is this the case? Our review shows that this is associated with worse outcomes all round, including increased risk of death.

A systematic review by Rodriguez-Arrastia et al in 2021 helps to answer this.63

They studied RCTs where probiotics had been given to adults as therapeutics to treat oncology treatment-related side effects. 20 clinical trials from 1998-2020 were included. 17 of these (85%) “revealed predominantly positive results” and 3 (15%) “reported no impact in their findings”.

10 of the studies used a single probiotic strain and the remaining 10 used 2 or more combined.

Probiotics commonly used capsules, gelatine and yoghurts for administration.

Length of administration varied from 1 to 24 weeks and dose from 106 to 1011 CFU/day. 4 weeks was considered the minimum length of time needed in the studies to observe and confirm beneficial effects.

Were there any significant side effects in the studies? There were, but these were not caused by the probiotics but by the oncology treatments or lactulose being administered. The meta-analyses showed how probiotics could work to reduce treatment related AE’s, including those caused by a weakened immune system:

Gastrointestinal side effects.

Immune-related side effects.

Inflammatory-related side effects.

Performance status-related side effects (patients’ general well-being and activities of daily life).

More proactive advice is to talk to your healthcare provider before taking them, particularly if you are being given immune checkpoint blockade treatments (anti PD-1 antibodies) or have a central venous catheter (CVC).64

Other therapeutics

Pomegranate juice

This study from 2006 by Adams et al is paywalled, unfortunately, but it tells us most of what we need to know about pomegranate juice from the title:

“Pomegranate juice, total pomegranate ellagitannins, and punicalagin suppress inflammatory cell signaling in colon cancer cells.“65

The authors discuss how phytochemicals from pomegranate (Punica granatum L) can inhibit cancer cell proliferation and promote apoptosis by modulating signalling proteins and transcription factors. They studied the effects of polyphenols from the fruit on the HT-29 human colon cancer cell line.

They found that pomegranate juice (PJ), tannin extract (TPT) and punicalagin downregulated several cancer associated pathways when the cells were exposed at a concentration of 50 mg/L of PJ. In this case another pomegranate polyphenol called ellagic acid (EA) was not effective, but other studies have shown efficacy when used in the treatment of tumours.66

Quercetin

In 2021 Uyanga et al reviewed how the potent flavonoid quercetin can be beneficial for gut microbiota and function.67 Citrulline is one of the three dietary amino acids in the urea cycle and acts as a functional gut biomarker.

Working synergistically, both of these possess anti-inflammatory, anti-oxidative, and immunomodulatory properties and can help prevent intestinal permeability and disruption to gut microbiota. Other benefits include helping to maintain intestinal immune tolerance as well as gut health in general.

Not by coincidence, both also possess significant anti-cancer properties.68 69 70

There are many many other supplements and foods which help to prevent CRC, but flavonoids and polyphenols are some of the more important ones.

Further reading

Probiotics to treat IBS:

Probiotics in Irritable Bowel Syndrome: An Up-to-Date Systematic Review

I can keep adding to this list:

Characterization of microbiota of naturally fermented sauerkraut by high-throughput sequencing

Health Effects of Coffee: Mechanism Unraveled?

You can take your magnesium supplements with probiotics. In fact it’s better if you do. The two work synergistically as probiotic bacteria promote magnesium uptake and magnesium promotes probiotic bacteria:

Effects of probiotic and magnesium co-supplementation on mood, cognition, intestinal barrier function and inflammation in individuals with obesity and depressed mood: A randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial

Probiotic-driven advancement: Exploring the intricacies of mineral absorption in the human body

Dietary Magnesium Alleviates Experimental Murine Colitis through Modulation of Gut Microbiota

The “Cancer Act 1939”: No grifting!

…Nobody (including limited companies) can publish any advert – meaning a notice, circular, label, wrapper or other document, or any announcement made orally or by any means of producing or transmitting sounds – aimed at the public, offering to treat anyone for cancer, to prescribe any treatments for the disease, or to give advice in connection to cancer treatment.

…Implicit in the term ‘advertisement’ is that there is a financial incentive: a person or company is selling something (whether it’s an actual treatment or regime, or advice about treating the disease) claiming to treat cancer.

Source: “The 1939 Cancer Act: What is it, what does it do, and is it ‘suppressing the cure’?”

https://news.cancerresearchuk.org/2016/02/19/the-1939-cancer-act/

Therapeutics and repurposed drugs for the treatment of cancer

Updates: 23rd November ‘22: Link to full literature review of baicalin. 1st January ‘23: Hyperlinks added (browser support varies). 26th January ‘23: GcMAF. 17th February ‘23: Fenbendazole. 10th March ‘23: Link added to the Substack on therapeutic interactions with lncRNAs.

Hat tip to Maria:

(https://mariagutschi.substack.com/)

Effect of the Short-Term Use of Fluoroquinolone and β-Lactam Antibiotics on Mouse Gut Microbiota

Disclaimer

This site is strictly an information website reviewing research into potential therapeutic agents. It does not advertise anything, provide medical advice, diagnosis or treatment. This site is not promoting any of these as potential treatments or offers any claims for efficacy. Its content is aimed at researchers, registered medical practitioners, nurses or pharmacists. This content is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition. Never disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something you have read on this website. Always consult a qualified health provider before introducing or stopping any medications as any possible drug interactions or effects will need to be considered.

Any extracts used in the previous article are for non-commercial research and educational purposes only and may be subject to copyright from their respective owners.

References

Rebersek M. Gut microbiome and its role in colorectal cancer. BMC Cancer. 2021;21:1325. doi:10.1186/s12885-021-09054-2

Chen S, Cao Z, Prettner K, et al. Estimates and Projections of the Global Economic Cost of 29 Cancers in 204 Countries and Territories From 2020 to 2050. JAMA Oncology. 2023;9(4):465-472. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2022.7826

Cassidy, Jim, and others (eds), Oxford Handbook of Oncology, 4 edn, Oxford Medical Handbooks (Oxford, 2015; online edn, Oxford Academic, 1 Sept. 2015): 300-310. https://doi.org/10.1093/med/9780199689842.001.0001, accessed 13 Feb. 2024.

Haggar FA, Boushey RP. Colorectal Cancer Epidemiology: Incidence, Mortality, Survival, and Risk Factors. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2009;22(4):191-197. doi:10.1055/s-0029-1242458

Hill DA, Furman WL, Billups CA, et al. Colorectal Carcinoma in Childhood and Adolescence: A Clinicopathologic Review. JCO. 2007;25(36):5808-5814. doi:10.1200/JCO.2007.12.6102

Backes Y, Seerden TCJ, van Gestel RSFE, et al. Tumor Seeding During Colonoscopy as a Possible Cause for Metachronous Colorectal Cancer. Gastroenterology. 2019;157(5):1222-1232.e4. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2019.07.062

Issaka RB, Inadomi JM. Low-Value Colorectal Cancer Screening: Too Much of a Good Thing? JAMA Network Open. 2018;1(8):e185445. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.5445

Bretthauer M, Løberg M, Wieszczy P, et al. Effect of Colonoscopy Screening on Risks of Colorectal Cancer and Related Death. N Engl J Med. 2022;387(17):1547-1556. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2208375

Causes of bowel cancer. nhs.uk. Published March 22, 2023. Accessed February 14, 2024. https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/bowel-cancer/causes/

Hofseth LJ, Hebert JR, Chanda A, et al. Early-onset colorectal cancer: initial clues and current views. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;17(6):352-364. doi:10.1038/s41575-019-0253-4

Mauri G, Sartore-Bianchi A, Russo AG, Marsoni S, Bardelli A, Siena S. Early-onset colorectal cancer in young individuals. Mol Oncol. 2019;13(2):109-131. doi:10.1002/1878-0261.12417

Rebersek M. Gut microbiome and its role in colorectal cancer. BMC Cancer. 2021;21:1325. doi:10.1186/s12885-021-09054-2

Mayorga-Ramos A, Barba-Ostria C, Simancas-Racines D, Guamán LP. Protective role of butyrate in obesity and diabetes: New insights. Frontiers in Nutrition. 2022;9. Accessed February 24, 2024. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnut.2022.1067647

How We Treat Left-Sided vs Right-Sided Colon Cancer – Hematology & Oncology. Accessed February 24, 2024. https://www.hematologyandoncology.net/archives/may-2020/how-we-treat-left-sided-vs-right-sided-colon-cancer/

Chen J, Wright K, Davis JM, et al. An expansion of rare lineage intestinal microbes characterizes rheumatoid arthritis. Genome Med. 2016;8:43. doi:10.1186/s13073-016-0299-7

Alpizar-Rodriguez D, Lesker TR, Gronow A, et al. Prevotella copri in individuals at risk for rheumatoid arthritis. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 2019;78(5):590-593. doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-214514

Collinsella aerofaciens - an overview | ScienceDirect Topics. Accessed February 17, 2024. https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/medicine-and-dentistry/collinsella-aerofaciens

Hwang CY, Cho BC, Kang JK, Park J, Hardies SC. Genomic Analysis of Two Cold-Active Pseudoalteromonas Phages Isolated from the Continental Shelf in the Arctic Ocean. Viruses. 2023;15(10):2061. doi:10.3390/v15102061

Eroğlu İ, Eroğlu BÇ, Güven GS. Altered tryptophan absorption and metabolism could underlie long-term symptoms in survivors of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Nutrition. 2021;90:111308. doi:10.1016/j.nut.2021.111308

Dehhaghi M, Kazemi Shariat Panahi H, Heng B, Guillemin GJ. The Gut Microbiota, Kynurenine Pathway, and Immune System Interaction in the Development of Brain Cancer. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2020;8:562812. doi:10.3389/fcell.2020.562812

Dehhaghi M, Kazemi Shariat Panahi H, Heng B, Guillemin GJ. The Gut Microbiota, Kynurenine Pathway, and Immune System Interaction in the Development of Brain Cancer. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2020;8:562812. doi:10.3389/fcell.2020.562812

Wyatt M, Greathouse KL. Targeting Dietary and Microbial Tryptophan-Indole Metabolism as Therapeutic Approaches to Colon Cancer. Nutrients. 2021;13(4):1189. doi:10.3390/nu13041189

Nucleotide Salvage - an overview | ScienceDirect Topics. Accessed February 16, 2024. https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/biochemistry-genetics-and-molecular-biology/nucleotide-salvage

Scott TA, Quintaneiro LM, Norvaisas P, et al. Host-Microbe Co-metabolism Dictates Cancer Drug Efficacy in C. elegans. Cell. 2017;169(3):442-456.e18. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2017.03.040

Nucleotides in Food. Accessed February 16, 2024. https://www.novocib.com/Nucleotide_Analysis_Services.html

Machover D, Goldschmidt E, Almohamad W, et al. Pharmacologic modulation of 5-fluorouracil by folinic acid and pyridoxine for treatment of patients with advanced breast carcinoma. Sci Rep. 2022;12:9079. doi:10.1038/s41598-022-12998-5

Liu Y, Lau HCH, Cheng WY, Yu J. Gut Microbiome in Colorectal Cancer: Clinical Diagnosis and Treatment. Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics. 2023;21(1):84-96. doi:10.1016/j.gpb.2022.07.002

Antineoplastic Antibiotic - an overview | ScienceDirect Topics. Accessed February 19, 2024. https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/pharmacology-toxicology-and-pharmaceutical-science/antineoplastic-antibiotic

Stein A, Arnold D. Oxaliplatin: a review of approved uses. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2012;13(1):125-137. doi:10.1517/14656566.2012.643870

Hsu HH, Chen MC, Baskaran R, et al. Oxaliplatin resistance in colorectal cancer cells is mediated via activation of ABCG2 to alleviate ER stress induced apoptosis. J Cell Physiol. 2018;233(7):5458-5467. doi:10.1002/jcp.26406

Iida N, Dzutsev A, Stewart CA, et al. Commensal Bacteria Control Cancer Response to Therapy by Modulating the Tumor Microenvironment. Science (New York, NY). 2013;342(6161):967. doi:10.1126/science.1240527

Yang J, Liu K xiong, Qu J ming, Wang X dan. The changes induced by cyclophosphamide in intestinal barrier and microflora in mice. Eur J Pharmacol. 2013;714(1-3):120-124. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2013.06.006

Bosetti C, Santucci C, Gallus S, Martinetti M, Vecchia CL. Aspirin and the risk of colorectal and other digestive tract cancers: an updated meta-analysis through 2019. Annals of Oncology. 2020;31(5):558-568. doi:10.1016/j.annonc.2020.02.012

Rohwer N, Kühl AA, Ostermann AI, et al. Effects of chronic low‐dose aspirin treatment on tumor prevention in three mouse models of intestinal tumorigenesis. Cancer Med. 2020;9(7):2535-2550. doi:10.1002/cam4.2881

Sakai SA, Aoshima M, Sawada K, et al. Fecal microbiota in patients with a stoma decreases anaerobic bacteria and alters taxonomic and functional diversities. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology. 2022;12. Accessed February 14, 2024. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcimb.2022.925444

Nagata N, Tohya M, Fukuda S, et al. Effects of bowel preparation on the human gut microbiome and metabolome. Sci Rep. 2019;9:4042. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-40182-9

Azcárate-Peril MA, Sikes M, Bruno-Bárcena JM. The intestinal microbiota, gastrointestinal environment and colorectal cancer: a putative role for probiotics in prevention of colorectal cancer? Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2011;301(3):G401-G424. doi:10.1152/ajpgi.00110.2011

Park IJ, Lee JH, Kye BH, et al. Effects of PrObiotics on the Symptoms and Surgical ouTComes after Anterior REsection of Colon Cancer (POSTCARE): A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. J Clin Med. 2020;9(7):2181. doi:10.3390/jcm9072181

Fasano A. Zonulin and Its Regulation of Intestinal Barrier Function: The Biological Door to Inflammation, Autoimmunity, and Cancer. Physiological Reviews. 2011;91(1):151-175. doi:10.1152/physrev.00003.2008

Pitsillides L, Pellino G, Tekkis P, Kontovounisios C. The Effect of Perioperative Administration of Probiotics on Colorectal Cancer Surgery Outcomes. Nutrients. 2021;13(5):1451. doi:10.3390/nu13051451

Wu HJ, Wu E. The role of gut microbiota in immune homeostasis and autoimmunity. Gut Microbes. 2012;3(1):4-14. doi:10.4161/gmic.19320

Turnbaugh PJ, Ridaura VK, Faith JJ, Rey FE, Knight R, Gordon JI. The effect of diet on the human gut microbiome: a metagenomic analysis in humanized gnotobiotic mice. Sci Transl Med. 2009;1(6):6ra14. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.3000322

De Filippo C, Cavalieri D, Di Paola M, et al. Impact of diet in shaping gut microbiota revealed by a comparative study in children from Europe and rural Africa. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(33):14691-14696. doi:10.1073/pnas.1005963107

Alam C, Valkonen S, Palagani V, Jalava J, Eerola E, Hänninen A. Inflammatory tendencies and overproduction of IL-17 in the colon of young NOD mice are counteracted with diet change. Diabetes. 2010;59(9):2237-2246. doi:10.2337/db10-0147

Hill DA, Hoffmann C, Abt MC, et al. Metagenomic analyses reveal antibiotic-induced temporal and spatial changes in intestinal microbiota with associated alterations in immune cell homeostasis. Mucosal Immunol. 2010;3(2):148-158. doi:10.1038/mi.2009.132

Penders J, Thijs C, Vink C, et al. Factors influencing the composition of the intestinal microbiota in early infancy. Pediatrics. 2006;118(2):511-521. doi:10.1542/peds.2005-2824

Caesarean section delivery and the risk of allergic disorders in childhood - PubMed. Accessed February 22, 2024. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16297144/

Hammer DP. Intestinal flora after colonoscopy: How to rebuild it. BIOMES - Feel better. Published December 9, 2019. Accessed February 14, 2024. https://biomes.world/en/interesting-facts/intestine/intestinal-flora/building-intestinal-flora/after-colonoscopy/

Philadelphia TCH of. Food as Medicine: Prebiotic Foods. Published December 21, 2022. Accessed February 22, 2024. https://www.chop.edu/health-resources/food-medicine-prebiotic-foods

Office of Dietary Supplements - Probiotics. Accessed February 20, 2024. https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/Probiotics-HealthProfessional/

Scharl M, Geisel S, Vavricka SR, Rogler G. Dying in yoghurt: the number of living bacteria in probiotic yoghurt decreases under exposure to room temperature. Digestion. 2011;83(1-2):13-17. doi:10.1159/000308715

Ferdousi R, Rouhi M, Mohammadi R, Mortazavian AM, Khosravi-Darani K, Homayouni Rad A. Evaluation of Probiotic Survivability in Yogurt Exposed To Cold Chain Interruption. Iran J Pharm Res. 2013;12(Suppl):139-144. Accessed February 22, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3813376/

Culpepper T. The Effects of Kefir and Kefir Components on Immune and Metabolic Physiology in Pre-Clinical Studies: A Narrative Review. Cureus. 14(8):e27768. doi:10.7759/cureus.27768

Ritchie ML, Romanuk TN. A Meta-Analysis of Probiotic Efficacy for Gastrointestinal Diseases. PLoS One. 2012;7(4):e34938. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0034938

Pouchitis - Symptoms and causes. Mayo Clinic. Accessed February 22, 2024. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/pouchitis/symptoms-causes/syc-20361991

Purton T, Staskova L, Lane MM, et al. Prebiotic and probiotic supplementation and the tryptophan-kynurenine pathway: A systematic review and meta analysis. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2021;123:1-13. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2020.12.026

Yan R, Wang K, Wang Q, et al. Probiotic Lactobacillus casei Shirota prevents acute liver injury by reshaping the gut microbiota to alleviate excessive inflammation and metabolic disorders. Microb Biotechnol. 2021;15(1):247-261. doi:10.1111/1751-7915.13750

Kato-Kataoka A, Nishida K, Takada M, et al. Fermented Milk Containing Lactobacillus casei Strain Shirota Preserves the Diversity of the Gut Microbiota and Relieves Abdominal Dysfunction in Healthy Medical Students Exposed to Academic Stress. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2016;82(12):3649-3658. doi:10.1128/AEM.04134-15

Wexler HM. Bacteroides: the Good, the Bad, and the Nitty-Gritty. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2007;20(4):593-621. doi:10.1128/CMR.00008-07

Rodriguez-Arrastia M, Martinez-Ortigosa A, Rueda-Ruzafa L, Folch Ayora A, Ropero-Padilla C. Probiotic Supplements on Oncology Patients’ Treatment-Related Side Effects: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(8):4265. doi:10.3390/ijerph18084265

Probiotics | Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. Published May 17, 2023. Accessed February 23, 2024. https://www.mskcc.org/cancer-care/integrative-medicine/herbs/probiotics-01

Adams LS, Seeram NP, Aggarwal BB, Takada Y, Sand D, Heber D. Pomegranate juice, total pomegranate ellagitannins, and punicalagin suppress inflammatory cell signaling in colon cancer cells. J Agric Food Chem. 2006;54(3):980-985. doi:10.1021/jf052005r

Lu G, Wang X, Cheng M, Wang S, Ma K. The multifaceted mechanisms of ellagic acid in the treatment of tumors: State-of-the-art. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy. 2023;165:115132. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2023.115132

Uyanga VA, Amevor FK, Liu M, Cui Z, Zhao X, Lin H. Potential Implications of Citrulline and Quercetin on Gut Functioning of Monogastric Animals and Humans: A Comprehensive Review. Nutrients. 2021;13(11):3782. doi:10.3390/nu13113782

Eren CY, Gurer HG, Gursoy OO, Sezer CV. Antitumor Effects of L-citrulline on Hela Cervical Cancer Cell Lines. Anticancer Agents Med Chem. 2022;22(18):3157-3162. doi:10.2174/1871520622666220426101409

Lotfi N, Yousefi Z, Golabi M, et al. The potential anti-cancer effects of quercetin on blood, prostate and lung cancers: An update. Frontiers in Immunology. 2023;14. Accessed February 22, 2024. https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/immunology/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2023.1077531

Health Effects of Coffee: Mechanism Unraveled?

...Coffee plays a dominant role in that regard because it is the major dietary source of phenolic acids and polyphenols in the developed world. A possible supportive action may be the modulation of the gut microbiota by non-digested prebiotic constituents of coffee, but the available data are still scarce. We conclude that coffee employs similar pathways of promoting health as assumed for other vegetables and fruits. Coffee beans may be viewed as healthy vegetable food and a main supplier of dietary phenolic phytochemicals.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7353358/

Some antibiotics are worse for the microbiome than others. The quinolones have to be the worst.

Great review, thanks